Many English-speaking cinephiles will watch films from all over the world; only the most ethnocentric cinephile will sneer at foreign-language films, ignoring richly-told stories from around the world (subtitles are not your enemy!). But what about films that use artificially created languages? Forget fictional languages like Elvish or Klingon (loved by nerds and linguists alike), there’s Esperanto, a fully-formed language developed by a Polish ophthalmologist, L. L. Zamenhof, in 1887. It’s notable because he developed the language as an effort to unify a world-weary of repeated armed conflicts in the late 19th century; a language designed to be a second language used by humanity to bring people together in fellowship, pre-dating the League of Nations and the United Nations by many decades. While Esperanto is still used by scholars and eccentrics, it was the basis for two films, one French, Angoroj (1964), a crime film, and one American, Incubus (1966), a surreal black-and-white horror film that was lost for decades until its re-discovery in France in the late 1990s. The use of Esperanto and influence from European cinema enhance the latter film’s basic tale of good vs. evil, replete with succubi, the titular creature, and a legendary “curse” that affected the film crew.

Incubus was directed by veteran film/TV writer Leslie Stevens, the man who created the classic science-fiction anthology TV series, The Outer Limits (1963-1965). Dissatisfied with the TV network interference that led to the series’s premature cancellation, Stevens retreated from the medium, penning a horror script that would be his third feature as writer/director. Stevens employed many of his Outer Limits crew (including future Oscar-winning cinematographer Conrad Hall and composer Dominic Frontiere), and even hired former Outer Limits guest star William Shatner, who was between acting gigs, as the lead actor (he would follow up Incubus with a TV pilot for some show called Star Trek). Fascinated with Esperanto and obsessed with the occult and New Age beliefs (as well as the great European art house films from the 1940s and 1950s), Stevens wanted to make a film that would stand out from standard Hollywood fare, discovering that over seven million people spoke Esperanto. Despite the producer’s hesitancy, it was agreed to film in Esperanto (the script, written in English, was given to the cast to understand the film’s context, and then a shooting script had English on one side and the translated Esperanto on the other). Filmed in black and white (in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio) with a meager budget of $125,000, Stevens and his small crew filmed their dreamy horror film in Big Sur and Monterey, California.

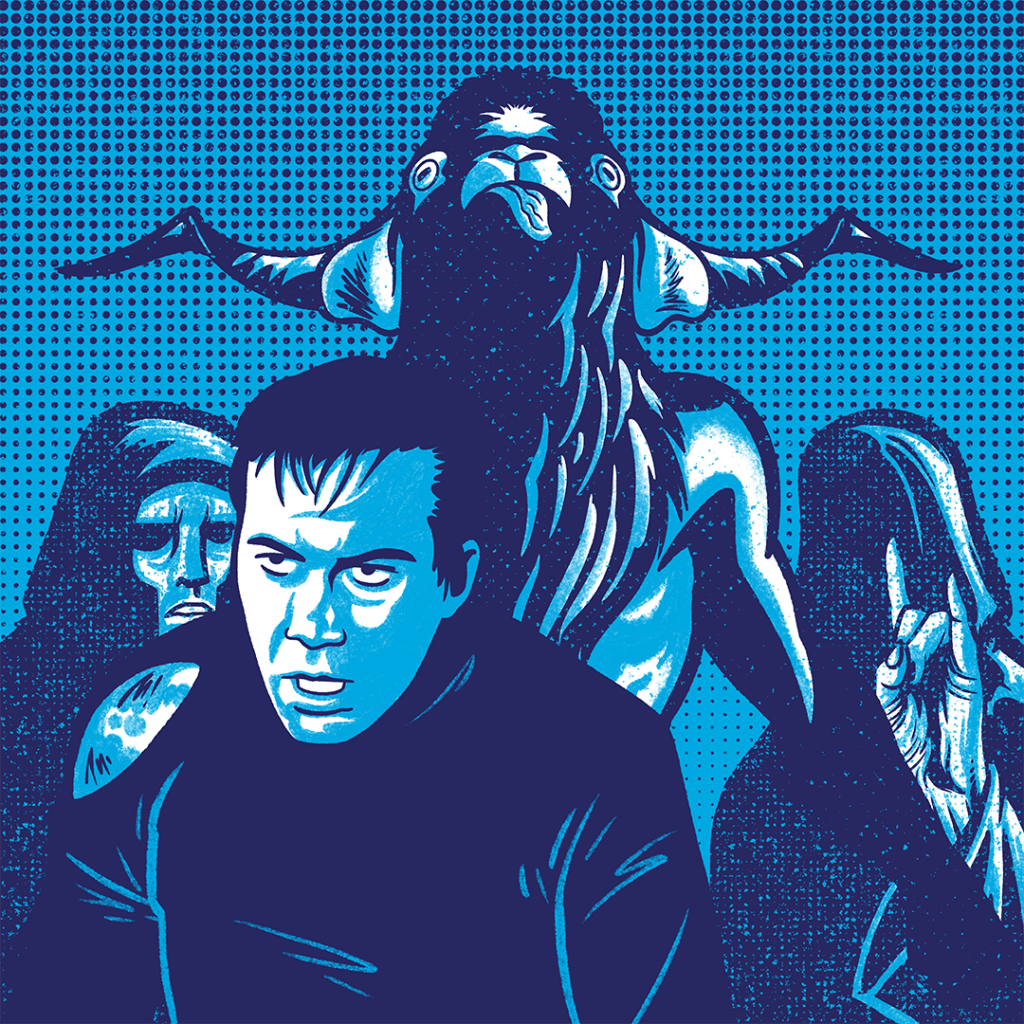

In the village of Nomen Tuum (Latin for “your name”), there exists a well that is believed to heal people and give them “subtle beauty”. Consequently, it attracts “the vain, the infirm, the corrupt,” which in turn attracts a coven of succubi, demons in female form who steal souls from men. Kia (Allyson Ames), a defiant succubus, wants to corrupt Marc (William Shatner), a soldier who has come home recently from war to tend his farm with his sister, Arndis (Ann Atmar). She is warned by a fellow succubus, Amael (Eloise Hardt), that Marc’s soul is too pure to corrupt and steal. Ignoring her, Kia appears to Marc as a weary traveler, and he is instantly smitten. Kia falls in love with Marc, and Amael, horrified, unleashes an incubus (Milos Milos) to destroy Marc, in retribution for his corruption of Kia!

Incubus’s low budget, TV crew, and short running time (78 minutes), as well as supernatural subject matter, makes it like an unofficial Outer Limits episode. The series dealt with a mélange of science-fiction and horror, often featuring some of the boldest creature effects seen on any screen at that time (I assume recreational drugs were more potent in the early ’60s). So a tale of good vs. evil, love, redemption, and succubi seems like a good fit (particularly with Season One’s “The Form of Things Unknown”, an equally dreamy–also lensed by Conrad Hall–sci-fi-flavored horror tale about a time machine, Vera Miles, and murder). I had first heard of Incubus from my tattered childhood copy of The Outer Limits Companion (yeah, I was that weird kid who read books devoted to analyzing his favorite ‘60s TV shows), by noted horror writer David J. Schow, and I was intrigued, but, alas, the film’s status as “lost” prevented me from seeing it (much like Outer Limits producer and Psycho screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s The Ghost of Sierra de Cobre, a supernatural film starring Martin Landau that’s also mentioned in the book and never available to me to see until the wonderful people at Kino Lorber recently released a Blu-ray). What makes the film distinctive from the TV series is the amount of location shooting and lack of sets, adding authenticity to a tale whose setting is kept vague intentionally, creating a timeless quality, a fable about the power of love (with apologies to Huey Lewis).

In his commentary for the Incubus DVD, William Shatner cites Leslie Stevens’s “strange imagination” as a reason he signed on to the film; it’s that strangeness that laid the foundation for much of his film and TV work, inspiring other writers to craft otherworldly tales on The Outer Limits, and the disco-flavored, tongue-in-cheek approach to adapting Buck Rogers in the 25th Century for a post-Star Wars audience. Incubus allows Stevens to poke around the well-worn good vs. evil archetype with style and moody lighting. Watching William Shatner speak in Esperanto, not his native English and French, is distracting at first, but the feeling quickly dissipates as one is drawn into the narrative. The film’s supernatural content and references to the Devil precede the wave of “Satanic Panic” movies that were popularized by Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist in the late ’60s and early ’70s (and the first of two “Satanic Panic” films for Shatner, the other being the outrageously fun The Devil’s Rain (1975), in which a shirtless, histrionic Shatner is offered as a sacrifice by head Satanist Ernest Borgnine). What’s fascinating to note is that although the film’s succubi are in league with the Devil, at no point in the film are the words “Devil” or “Satan” ever used. The succubi refer to the “Lord of the Night”, “God of Darkness”, and “Beast God”, which are suitably formidable noms de plume for the Prince of Darkness, who appears to be content to stay out of sight and accept the succubi’s gifts of corrupted souls gladly. The depiction of succubi as creatures who take the form of very blonde Scandinavian women is a fun twist on convention—no vampish-looking ghouls trying to secure and offload valuable souls in this picture! The title “Incubus” is misleading, considering the number of succubi who lurk about the beaches—the titular creature doesn’t appear in the film until the halfway mark! From a marketing standpoint, I’m sure “Incubus” as a title was more intriguing and mysterious compared to “Succubus,” which just sounds naughty—you get two types of creatures for the price of one!

The performances by the main cast help sell the film’s timeless quality. Kia is a headstrong and formidable succubus, and Allyson Ames does a marvelous job portraying a demon who sees William Shatner’s Marc as a challenge, a soul worthy of the risk of upsetting the balance between Heaven and Hell. “I would be the Beast Daughter’s best daughter,” she says, intent on corrupting an incorruptible soul. We already know she’s very good at her job—she lures and drowns a local drunkard at the beach at the beginning of the film with little effort (it’s a beautiful POV shot looking up at Kia as she smiles and holds the drunkard’s head down with her leg, as the ocean washes over the camera). Kia is obsessed with Marc, and Ames transforms her from a calculating succubus to one who is “corrupted” by Marc’s goodness and “befouled by love” (as Amael describes it). Her fear is palpable when Marc carries her sleeping form from the beach to the local church, as she awakens to close-ups of Catholic iconography, which would comfort many a person, but for a succubus, is the antithesis of her existence.

William Shatner is equally good as the pure and noble Marc, a rationalist not prone to superstition–he ridicules the alleged healing claims of the village’s well and explains to Kia that an eclipse is not an omen, but merely an astronomical phenomenon. Marc has already been described by Amael as a hero who cannot be corrupted, and it’s not hard to see why: he’s a selfless soldier who has saved his comrades during combat, yet despite an injury that causes him some visible discomfort, his jovial spirit isn’t affected by the war or walking in the woods to the well. Shatner imbues Marc with a quiet soulfulness; he’s a man who feels content to live on a farm with his sister. He’s friendly, offering food, drink, and lodging to a total stranger (perhaps a bit too trustworthy, as his welcoming nature does cause harm to his sister). He’s able to resist Kia’s tempting offer to lie naked on the beach and frolic in their collective nudity: “I want us to be together, to stay together, as man and woman…the right way…our bodies mean very little unless we give our souls to love.” Despite Amel and Kia’s vengeance, Marc is able to overcome his anguish over his sister’s death and the “death” of the incubus, persevering and clinging to his faith, “My soul belongs to God.” His belief is so strong that he’s able to win Kia over from her inherent dark nature and renounce her evil ways—now that’s love.

Conrad Hall’s cinematography is one of the reasons The Outer Limits is still remembered over 50 years later, and it’s his work in Incubus that cements its fabulist quality. The natural locations around Big Sur are perfect to create a modern fable: a dark forest, an open field, a long and winding beach, and an old missionary church. The night and day shots and lighting are clearly influenced by European cinema, from Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Sign (the minimalist black cloaks of choice for the ever-fashionable succubus is a clear nod to Bergman’s film). The film mixes night and day-for-night shots and stock footage of an eclipse (an omen of things to come, despite Marc’s insistence to the contrary). Hall uses soft lighting and mist to convey the dream-like, fabulist mood, one in which our characters are isolated by geography (other than the opening scene’s drunkard and some silent monks, no other villagers are shown—Marc and his sister are vulnerable to the succubi’s presence). When Marc brings Kia into the church, Hall’s jarring close-ups of Catholic iconography juxtapose the idea that a church is a sanctuary; to a succubus like Kia, it’s like being trapped in a pentagram. It’s Hall’s photography that makes Incubus a visual marvel despite its paltry budget. One of the most impressive scenes is when the succubi, led by Amael, conjure an incubus to the mortal plane in order to kill Marc. For just a few seconds, there is an image of the creature in its true form, with a wide demonic wingspan, but obscured by smoke, mist, and low lighting. It’s not just a budget limitation; it provides the viewer a hint of the incubus’s true form and a sense of dread—Marc is certainly doomed! The incubus takes human form, a man clad in black tights, and Star Trek fans will enjoy a bit of pre-Captain Kirk fight choreography, as Marc struggles against the demon. The climactic struggle between Kia and the incubus, now resurrected in goat form, is also beautifully shot, punctuated by Dominic Frontiere’s haunting score. Fans of Robert Eggers’s The Witch will experience serious Black Phillip vibes as Kia grapples with the incubus-turned goat at the doorway of the church—it’s a delicious scene indeed!

Despite its small budget, Incubus is a fascinating ode to fables and mythology, acknowledging its European influences while creating something unique with Esperanto. The experiment with a seldom-used, ancient-sounding language is audacious and strangely apropos for a coven of she-demons who wander the Earth. Leslie Stevens took a small amount of money and used his trusted Outer Limits crew to craft an atmospheric horror tale that doesn’t rely on ambitious creature effects to scare audiences. It’s fast-paced fabulist fare, and it’s worthy of attention. I’m glad eagle-eyed cinephiles discovered a sole print and rescued it. Ideally, the film should be rescued from standard-definition obscurity and given a high-definition afterlife, because it’s worth it.

According to William Shatner’s commentary, a “hippie” was incensed that the film crew invaded Big Sur, so he cursed the production.

“THE CURSE OF INCUBUS” (as listed on the DVD special features):

- Milo Milos (AKA the Incubus) dated Barbara Ann Thompson (estranged wife of Mickey Rooney) during filming. Less than a year later, their bodies were discovered in bed together, as Milos had murdered Thompson and then committed suicide.

- Ann Atmar (Arndis) committed suicide mere weeks after the film wrapped shooting.

- Eloise Hardt (Amael) discovered her daughter had been kidnapped from their driveway; the daughter’s murdered body was discovered a few weeks later.

- Leslie Stevens’s production company, Daystar, which produced The Outer Limits and other classic ’60s TV series, went bankrupt and his (third) marriage to Allyson Ames (Kia) ended.