IN DEFENSE OF: STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE

Fandom is a perplexing, frequently frustrating entity: it can be a supportive, passionate group of like-minded individuals who enjoy fictional characters on the page or on the small or big screens, but it can also be a fearsome mob mentality, one that turns on its worshiped creative idols with little provocation and much entitlement. George Lucas, J. K. Rowling, Peter Jackson, and the Game of Thrones showrunners, among others, have experienced fan anger because of specific creative choices made. Fans support creative endeavors, helping make a Star Wars become successful, filling a studio’s coffers and selling merchandise, but it’s the ownership of fictional characters that’s distorted: everybody has an opinion on how characters should be developed, but woe is the creator who defies the will of a few vociferous individuals for the sake of characterization. To be fair, some creative choices aren’t organic and subsequent constructive criticism has merit (particularly creative choices to alter existing creative works long after it has been in the hands of fans for decades–I’m looking directly at you, Mr. Lucas), but frequently, it’s the online trolls, a minority of fans, who scream vitriol the loudest, oblivious to decorum, decency, or good grammar. Star Trek, one of the oldest intellectual properties in Hollywood, has incurred fan anger, justified or not, repeatedly in its 53 years of exploring strange new worlds. One of the earliest moments of Star Trek fan anger occurred when Star Trek: The Motion Picture debuted on December 7, 1979, ten years after the TV series had been cancelled and sent to its rerun syndication afterlife. Though the film was a box-office success (adjusted for inflation, the film grossed over $400 million in North America), many Star Trek fans were unhappy, calling it “The Motion-less Picture” or “Star Trek: The Motion Sickness” for its lack of action scenes and emphasis on visual effects. In the wake of Star Wars or Close Encounters of the Third Kind, many critics found the film underwhelming, and Paramount Pictures, owner of Star Trek, was disappointed in the financial return on a $46 million budget (then the most expensive film at the time, ironic for a film based on a TV show). Despite its production budget, Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s profitability led to a sequel, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, on a calorie-reduced budget of $8 million. With its focus on space battles, Moby Dick quotes, and a snarling villain returning from the TV series (Season 1’s “The Space Seed”), TWOK grossed nearly as much as The Motion Picture, and led to a series of successful films, which in turn spawned Star Trek: The Next Generation and its own TV spinoffs and movies (that’s a lot of trekking). One of the biggest disappointments is that Paramount, in wanting an ambitious, heady plot to launch Star Trek on the big screen, gave in to pulpy galactic adventures to fill theater seats rather than fulfill Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry’s promise of social commentary in the guise of science fiction. Star Trek: The Motion Picture is better than most Star Trek fans or cinephiles remember, providing a refreshing rebuttal of Star Wars-inspired sci-fi swashbuckling prevalent in the late ’70s and early ’80s (and no, dear reader, this is not another case of Star Trek vs. Star Wars because that’s a tiresome and nonsensical argument—it is possible to enjoy both franchises). In 2001, Robert Wise was finally given the chance to edit the film the way he wanted, as time constraints in 1979 prevented him from performing judicious editing on some of the lingering visual effects sequences (the theatrical cut has long been considered more of a workprint, and Paramount released the film repeatedly on home video as “The Special Longer Version,” which added cut scenes, including visible parts of a set’s scaffolding, to pad the running time). Forty years later, it’s finally getting respect as the biggest and boldest cinematic Trek.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s release coincides with my own introduction to Star Trek as a five-year old: though I’d seen a few scenes of the TV series, I remembered its spooky music and the salt vampire (one of the few aliens not clad in togas), which terrified me. At the time, I was really into Star Wars and had plenty of the Kenner action figures, even the Millennium Falcon (much to my brother’s envy—he was given Boba Fett’s stupid-looking ship, so I can’t blame him feeling disappointed), so when my Aunt Donna took me to see Star Trek: The Motion Picture, I didn’t know what to expect. It was too loud for me, as I covered my ears with my hands, and the otherworldly, bombastic music scared me, as did the bumpy-headed Klingons and a vampiric-looking Mr. Spock; at least I got the Star Trek: The Motion Picture McDonald’s Happy Meal as a consolation prize (the first film tie-in Happy Meal!). Sadly, there was no toy, only an iron-on patch of the Starfleet arrowhead insignia, which my mom ironed on a plain blue shirt, albeit upside down (and yes, she still made me wear it to school—we weren’t flush with cash, so no shirt was going to be wasted unworn). Star Trek: The Motion Picture scared me, but it fed my interest in Star Trek. I would visit Aunt Donna often and be plopped in front of her massive wood-adorned TV set, watching Star Trek reruns recorded on Beta tapes. I grew to love the adventures of Kirk, Spock, and Bones, my holy trinity of fictional characters; although I wasn’t taken to see Star Trek II (it was thought to be too violent for me and remains to this day the only Star Trek film I haven’t seen on the big screen), I was excited when Aunt Donna bought the Beta videocassette (for $80!) and screened it for my family. I grew up and developed a taste for literature and film, but I never stopped enjoying Star Trek—I’ve seen all the films and nearly all the episodes (including Discovery). If you ply me with drinks, I might confess that I know all 79 original episodes by their episode titles (from “The Cage” to “Turnabout Intruder”, courtesy of memorizing Alan Asherman’s Star Trek Compendium), or that I read a lot of the Star Trek novels (including movie novelizations) before I became a snooty English major. Star Trek: The Motion Picture is still the Star Trek film I revisit the most, and its reputation as a mediocre film by fandom is why I feel compelled to defend it as a genuinely remarkable piece of cinema.

Nobody other than rabid Trekkies (“They can’t tell me what to call them,” Gene Siskel announced haughtily on an episode of Siskel and Ebert) would confuse the Star Trek films as being cinematic works of art; they are amusing time capsules of ’80s Hollywood sci-fi. Unlike the sci-fi horrors of the Alien films and The Thing, and the bleak dystopian science fiction of Blade Runner, the Star Trek films are light cosmic adventures that have little to say (other than playful banter between Bones and Spock), and have plenty of space battles, courtesy of George Lucas’ Industrial Light and Magic special effects company. While Luke Skywalker was whining about his parentage and contemplating incest, James Tiberius Kirk was outsmarting a 20th century genetically-engineered madman, stealing the Enterprise, fighting Christopher Lloyd’s Klingon in a planet-side tête-à-tête, saving humpback whales from extinction, foiling an intergalactic assassination attempt, and asking the question that has frustrated philosophers for centuries: What does God need with a starship? The Star Trek films were an opportunity for fans to revisit some of their favorite characters every couple of years, but they were never taken seriously as thoughtful science fiction by cinephiles or critics. Missing was the social commentary its creator, Gene Roddenberry, had instilled in the TV series. When the works of Philip K. Dick and Frank Herbert were adapted for the big screen by acclaimed filmmakers, having a starship crew of senior citizens seemed quaint in comparison. But in 1979, having a legendary filmmaker like Robert Wise take the helm of the redesigned USS Enterprise in Star Trek: The Motion Picture was quite the coup for Paramount, hoping for profits and prestige.

When a mysterious alien cloud destroys a fleet of Klingon battlecruisers, Starfleet discovers that the cloud is heading to Earth and even Spock, on Vulcan to purge his human half, can sense the alien presence. The only ship in range is the Enterprise, which is still being refitted. James T. Kirk, now an admiral for nearly three years after the Enterprise’s five-year mission ended, takes temporary command of the ship, demoting its captain, Will Decker, and recruiting a retired Dr. McCoy for the mission. En route, Spock arrives to help, but his motives are not necessarily altruistic. The Enterprise intercepts the alien intruder, V’Ger, which results in the death of the Enterprise’s navigator, Lt. Ilia. Through its mechanical facsimile of Ilia, V’Ger informs Kirk that it seeks its Creator, believed to be on Earth. V’Ger doesn’t think humans (“carbon units”) are true life forms, so it intends to eradicate all life on Earth in order to contact its Creator without interference.

What distinguishes Star Trek: the Motion Picture from its sequels is not just its groovy space-pajama-like uniforms with waist-level bio-readers (I love these uniforms, particularly Admiral Kirk’s regal two-piece, but not so much the cast—they requested, nay, demanded a uniform change in Star Trek II to nautical-themed maroon jackets and turtlenecks), but its acclaimed director, Robert Wise. As a former editor of Orson Welles’ films like Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, and an accomplished filmmaker (The Day the Earth Stood Still; Run Silent, Run Deep; The Haunting; West Side Story; The Andromeda Strain), Wise was a veteran of science-fiction cinema and knew how to handle a big film production deftly, particularly one with as a chaotic production as Star Trek: The Motion Picture. The first special effects company had been fired for mediocre work, setting back production by months, but Wise knew he could count on 2001 and Star Wars technical gurus Douglas Trumbull (whom Wise had worked with on Andromeda Strain) and John Dykstra to help the film make its December 7, 1979 due date (Paramount had guaranteed the film by this date to film exhibitors and a delay would cost the studio millions of dollars in breach of contract). They were already attuned to the new wave of visual effects techniques needed to relaunch the Enterprise. Wise was also instrumental in convincing Leonard Nimoy to return as Spock, something the actor had been extremely reluctant to do, as he was suing Paramount for using his likeness for merchandise without his consent (it was Wise’s wife and son, both Star Trek fans, who scoffed at Star Trek without Spock and convinced Wise otherwise). Wise kept his cool when producer Gene Roddenberry and screenwriter Harold Livingston butted heads as they revised the script daily, never cracking, never perspiring as cast members would arrive to set without the new pages of the script ready. It was Wise who made sure the film would be delivered on time.

“The human adventure…is just beginning,” Orson Welles’ baritone voice announced in darkened theaters for the teaser trailer of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, taking a cue from both Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Sergei Tarkovsky’s Solaris. While The Motion Picture is not to be confused with that “ultimate trip”, Kubrick’s influence, among others, can be seen in the film’s impressive production design. The TV series was partly inspired by Forbidden Planet (even substituting one Canadian captain, Leslie Nielsen, for another, William Shatner), the rare ’50s science fiction film that wasn’t a B-picture dealing with irradiated insects or hostile Martians. While the series was notable for its use of bold colors and soft lighting (particularly on female guest stars like The Godfather Part II’s Marianna Hill), a feature film version would need to reflect the change of aesthetic attitudes of the late ’70s, including show the size of the Enterprise from inside. Realizing a film production would require greater attention to detail on the big screen, Gene Roddenberry assembled many former 2001 technicians and craftspeople. Star Trek: The Motion Picture would take some of the established aspects of the TV series–production designer Walter “Matt” Jeffries’ iconic starship and bridge designs–with an updated futuristic look, befitting its sizeable budget, and the realism Kubrick sought in his film’s production designs. The Enterprise bridge’s sleek consoles, streamlined work stations, and multi-screen displays are not unlike those found on 2001’s Discovery, but with Starfleet flourishes (and the seats have what’s the closest thing to a seat belt, preventing most of the crew from flailing about like they did so expertly on TV). The recreation deck, a multi-level set in which the entire crew assembles for Kirk’s mission briefing is impressive, as the viewer can finally see the entire crew, something that had impossible on a TV budget. The transporter room is darkly lit and industrial, including a shielding area for the transporter technician (how much radiation emanates from 23rd century transporters?), befitting the enormous power required to beam people (and reflects how dangerous it is to disassemble people on a sub-atomic level with the horrifying-yet-effective scene that sees two crewpersons die in a transporter malfunction: “Enterprise, what we got back didn’t live long, fortunately,” Starfleet informs a shocked Admiral Kirk–Bones’ dislike of the transporter now seems very justified). The Engineering section is a brilliant construction of smoke and mirrors, using forced perspective, matte paintings, and children in engineering suits to convey the massive size of the warp engine powering the ship. A multi-level vertical shaft of swirling light and blinking consoles convincingly display the tremendous matter/anti-matter power needed to run a starship, something never convincingly done on the TV series. Scotty now seems very happy in the bustling Engineering section, ordering his lackeys about while the engines hum melodically. Again, like 2001 and Tarkovsky’s Solaris, the Enterprise sets are built for function, detail, and spatial minimalism, creating a realistic impression of possible future technology.

The V’Ger central complex set is an awesome sight, something that none of the subsequent sequels ever accomplished or attempted. V’Ger’s “brain”, the earth probe Voyager 6, is centered at the bottom of a bowl that’s surrounded by a complex pattern of brightly-lit panels, like surging electro-chemical brain impulses. The set is massive, as it should be, illustrating the living machine’s immense storage of knowledge accumulated over centuries, and it’s the crucial setting for the film’s climax, as V’Ger finally meets its Creator. The backdrop is pitch black, save for occasional flashes of lightning, a suitable contrast to the light intensity of the lower bowl complex. It’s another example of how the filmmakers used the film’s budget to tell a big story of a vast intelligence coming home. The set would have been prohibitively expensive for any of the sequels, so it’s rewarding to see Wise use it effectively, conjuring an epic cosmic entity that makes the human characters very small in comparison. Such scope and attention to detail, along with incredible visual effects, would aid the film in becoming a majestic space epic, one of exploration and greater insight into humanity. Regrettably, these details were quickly jettisoned when veteran TV producer Harvey Bennett was brought in to oversee Star Trek II and most of the subsequent sequels to keep costs down, using cheap interiors and recycled Star Trek: The Next Generation sets. The Star Trek films would still look impressive, but none of them have the luxurious production detail as Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

The newly-refurbished Enterprise, as filmed by Trumbull, is a splendid example of why practical special effects stand out from CGI, as she is breathtaking in scope, detail, and size (I invoke Maritime tradition in referring to the Enterprise in the feminine). One of the frequent complaints of fans and critics is that the flyby sequence in which Scotty reveals the new-look Enterprise to Kirk is too long. Roddenberry, Wise, and Trumbull knew that the starship was just as an important character as her crew, and deserved her own screen time; the camera pans longingly over the drive section, the two nacelles, shuttlecraft bay, and the saucer section, as fans could finally see details not achieved in the TV Enterprise model (hey, there’s an arboretum near the bottom of the drive section!). The Enterprise is Kirk’s obsession, his true love, and it’s befitting that he’s able to marvel at her makeover with languid camera shots (As Bones says later in the film, “I know engineers, they love to change things.”). It’s not just hull detail, but the ship’s self illumination that’s striking, especially as the ship ventures into the unknown to intercept V’Ger, a sole representative seeking contact in the vastness of space. The final shot of the Enterprise in the film, as the camera rotates around her contours (bookmarking a similar rotating shot of one of the Klingon ships in the film’s opening sequence), is spectacular, highlighting the dedication of overworked artists in bringing her to life on the big screen, just as she goes to warp speed in a paroxysmal streak of light.

As 2001 had revolutionized visual effects in cinema, so too had George Lucas done so with Star Wars—for contrast, watch Logan’s Run, a dystopian sci-fi film released a year before Star Wars, and you’ll be startled how dated its effects appear. With other space-set productions inspired by the sophistication of Star Wars’ visuals—Alien, The Black Hole, Superman–the work of Trumbull, Dykstra, and others is impressive. “It will startle your senses,” Orson Welles states in a trailer for The Motion Picture and the film delivers on that promise: whether it’s the destruction of a Klingon armada in the opening scene, the detailed space observatory station Epsilon 9, the Enterprise leaving drydock, the wormhole sequence, or Spock’s space walk, the universe looks big. As the Enterprise ventures deeper into V’Ger, its origin still a mystery, the size and magnitude of this cosmic living machine is pronounced by some of the greatest visual effects committed to celluloid. None of the subsequent sequels would have budgets big enough to accomplish such spectacles, and I think the special effects are awe-inspiring. I remind you: these are all practical effects. Computers were primitive in the late ’70s, so effects people had to use ingenuity, inventiveness, and imagination to create the effects, and they still look breathtaking. CGI is a wonderful tool, but it has yet to transport me to different worlds such as the ones seen in Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

One of the criticisms of Star Trek: The Motion Picture is that there isn’t much in the way of action-oriented scenes, but this was always a conscious choice by Roddenberry, Wise, and Paramount. Star Wars was the big space-fantasy spectacle, replete with light saber duels and laser dogfights, so Roddenberry did not wish to appear as a cash-in, like Battle Beyond the Stars, a low-budget Roger Corman knockoff, focusing on the TV series’ core premise that the Enterprise crew were peaceful explorers. As a voracious reader of science fiction, Roddenberry was friends with Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov and was very familiar with 2001’s co-writer, Arthur C. Clarke, and Stanislaw Lem, a notable Polish science fiction writer whose novel Solaris envisioned a sentient planet of water (The description of V’Ger as a sentient living machine is not dissimilar to Lem’s novel or the Tarkovsky adaptation, taking an abstract concept and concretizing it for narrative purposes). V’Ger, while a credible threat to humanity, was not considered evil and would be handled with reason; violence would be used only as a last resort. “There is no comparison” was a frequent tagline of the film’s marketing, acknowledging that the film was not to be confused with Star Wars, but as the by-product of loyal fandom for over a decade. The Motion Picture would illustrate that Starfleet personnel, unlike the ill-fated Klingons in the thrilling opening sequence, weren’t quick to fire photon torpedoes on a perceived threat. V’Ger has awesome power and it’s Kirk’s experience during the Enterprise’s five-year mission, along with Spock and Bones’ sage advice, that triumph over brute force. V’Ger, in amassing so much knowledge, has lost its purpose; there is nothing left to discover in the form of raw data. In the future, humanity doesn’t use violence to achieve results. Exploring V’Ger and its quest to evolve is much like the mysterious monolith and its manipulation of human evolution in 2001. The reveal that it’s humans who are V’Ger’s Creator is a logical conclusion: who better than a species of highly irrational beings can it continue to learn all that’s learn-able? An evolution that includes humanity and a living machine is heady stuff for a big-budget feature film then or now, and the film is to be applauded for countering the easy seat-filling of space battles with thoughtful plotting.

Another criticism of Star Trek: The Motion Picture is that it is cold, not just in its set design, but the depiction of beloved characters. One could argue that it’s a reflection of Gene Roddenberry: he hated the comedic Star Trek episodes. He wasn’t the active showrunner when scripts for “I, Mudd”, “The Trouble with Tribbles”, and “A Piece of the Action” were shot; though those comedy episodes are generally well liked by fans, not so by Mr. Roddenberry. Outside of the familiar bridge banter at the end of the film by Spock and Bones, Star Trek: The Motion Picture is devoid of humor, and it’s intentional. It’s not just Roddenberry wanting to tell a Kubrickian-style science fiction narrative, but it’s also the state of mind the characters are in as they reunite awkwardly for a cosmic crisis. Kirk is withering away as a bureaucrat; transitioning from galactic explorer to Chief of Starfleet Operations has not only made him “stale”, as he jokes to Scotty, but desperate to use the V’Ger Crisis as an opportunity to regain his command. It’s refreshing and painful to see Kirk flounder at his regained command, failing to understand the redesigned ship’s capabilities (which almost destroys the ship when they’re caught in a wormhole), acting defensively towards Decker, the younger man, his competition for command, or not knowing where the turbo-lifts are located. William Shatner’s acting as Kirk has been exaggerated so much by impressionists and comedians that it’s easy to forget how good he was in the TV series. Roddenberry modeled Kirk after C.S. Forrester’s noble 19th century British naval hero, Horatio Hornblower, and Shatner, a classically-trained actor, conveyed intelligence, confidence, vulnerability, compassion, and a healthy sense of humor, whether he was out-thinking a super-computer or romancing an alien woman to save his crew. In the film, Shatner’s Kirk is subdued, as he’s going through the 23rd century version of a mid-life crisis, clamoring for his old crew, and even forcing McCoy out of retirement with the “reserve activation clause”, something his old friend resents, yet accepts grudgingly. Kirk is astonished when Bones tells him that he’s driving his crew too hard—he’s over-compensating to hide his insecurity, a feeling he seldom knows. The scene in which he admonishes Decker privately for overriding his phaser order during the wormhole incident is particularly telling:

KIRK: All right, explanation? Why was my phaser order countermanded?

DECKER: Sir, the Enterprise redesign increases phaser power by channelling it through the main engines. When they went into anti-matter imbalance, the phasers were automatically cut off.

KIRK: Then you acted properly, of course.

DECKER: Thank you, sir…I’m sorry if I embarrassed you.

KIRK: You saved the ship.

DECKER: I’m aware of that, sir.

KIRK: Stop…competing with me, Decker!

DECKER: Permission to speak freely, sir?

KIRK: Granted.

DECKER: Sir, you haven’t logged a single star hour in two and a half years. That, plus your unfamiliarity with the ship’s redesign, in my opinion, seriously jeopardizes the mission.

KIRK: I trust you will…nursemaid me through these difficulties, Mister?

DECKER: Yes, sir. I’ll do that.”

McCOY: He may be right, Jim.

Kirk doesn’t have the confidence of his junior officer or his old friend, and the shot of him standing alone in his quarters, as the opaque door slides closed, shrouding him in darkness, is one of the best shots in the film.

Leonard Nimoy’s Spock in the film differs greatly from the TV series, but again, the character is at a different place than when we last saw him. At the beginning of the film, a surprisingly-disheveled Spock undergoes the Vulcan ritual of Kolinahr, the purging of all emotion, as his inner conflict to control his human half has come to a head. However, V’Ger’s consciousness calls out to him, a fellow being without purpose or meaning. Once again, Spock’s human half betrays him, and he fails the ritual. He returns to the only life he has known that’s given him purpose: Starfleet. Spock’s reintroduction in the film, as he boards the Enterprise in his vampiric Vulcan cloak, hair neatly cut, a completely imposing figure dwarfing Chekov at the airlock, contrasts that of his earlier appearance. He’s over-compensating, ignoring the all-too-human exclamations and greetings when he arrives on the bridge (even McCoy’s “Well, so help me, I’m actually pleased to see you!” is ignored). He would never admit it, but Spock is embarrassed at failing the Kolinahr, so he focuses his energies on contacting the entity that has called out to his human side, suppressing his emotions. His embarrassment is apparent in stiff posture and mannerisms: he has to be told repeatedly to sit down, and even when he complies, he looks constipated (which is hardly surprising, as Starfleet engineers haven’t added bathrooms on the Enterprise). Nimoy’s Spock here is a character seeking purpose, going so far as to steal a spacesuit and try to contact V’Ger personally. He explores its inner chambers, only to learn that it isn’t appropriate—or logical—to attempt a mind meld without first asking permission.

There are two fantastic scenes that demonstrate Spock’s growth as a character: his post-spacewalk Sickbay scene and a critical moment when it appears V’Ger will destroy the Earth. In the first scene, Spock can be heard laughing, and a surprised Kirk discovers a smiling Spock, still in shock from his disruptive mind meld. Spock realizes that through the meld, V’Ger is devoid of emotion and thus meaning. He finally admits his friendship with Kirk as a demonstration of a feeling that is utterly alien to the living machine. It’s a touching scene, and Nimoy and Shatner don’t overplay it, subtly showing the audience that their friendship has deeper meaning than what Spock has shown in prior scenes. The second scene allows what is a private moment for Spock to become known to the bridge staff: he’s crying. He informs Kirk and Decker that it’s for V’Ger—he and it have been on similar paths, but Spock has now resolved his human-Vulcan conflict quietly and has found his purpose, unlike V’Ger. It’s another understated moment that shows Spock’s depth of character. Inexplicably, this scene was cut from the theatrical version, much to Nimoy and Wise’s anger, but, thankfully, it’s restored in the Director’s Edition. Kirk and Spock are both in transitory places in their lives during the film and it’s a necessary step in connecting the past of the TV series in order to set course for their continued adventures on the big screen for well over a decade afterwards.

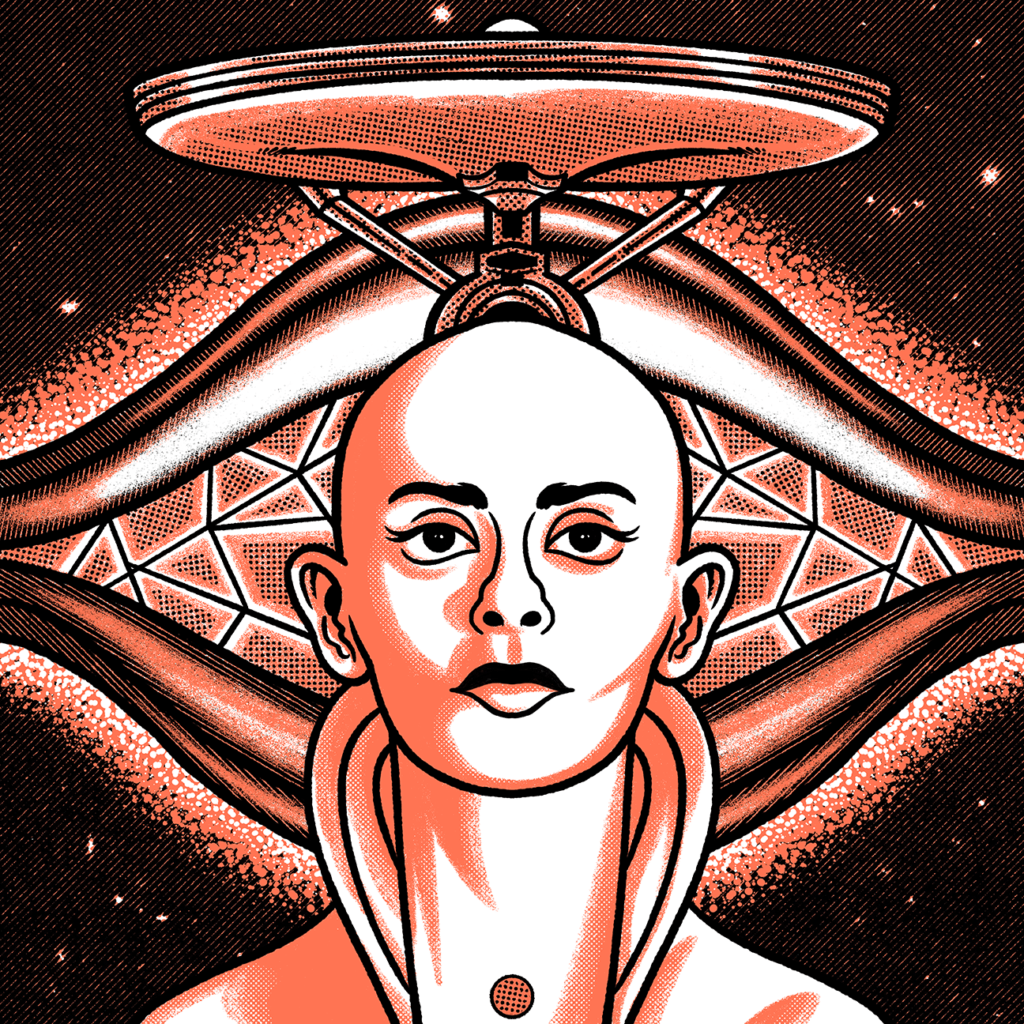

In addition to the returning TV cast, two new characters were added: the aforementioned Captain Will Decker (Stephen Collins) who deals with being demoted, and Lt. Ilia (Persis Khambata), a Deltan, a race of highly-sexually beings—Ilia cooly informs Kirk that her oath of celibacy is on record (in a cut scene added to the Special Longer Version, Sulu becomes flustered as he shows her the updated navigational console, so powerful are Deltan pheromones!). Decker and Ilia had a previous relationship, and there are still lingering feelings, but they agree to be professionals (if this sounds familiar, the characters were also the basis for Riker and Troi on Star Trek: The Next Generation). Decker and Ilia are integral to the film’s plot: just as Decker is competition for Kirk’s command, Ilia is killed and “resurrected” by V’Ger in order to communicate with the carbon units. As V’Ger’s eyes and ears, the Ilia probe is still breathtakingly beautiful, as she emerges from a sonic shower, but cooly logical and a bit creepy with her augmented electronic voice (Gene Roddenberry’s novelization of the film delves deeper into Deltan pheromones and their affect on the crew, particularly Kirk, who also has a “sex coach” prior to the mission; Roddenberry was known for being a bit of a gleeful hedonist and the novel’s 23rd century setting is very sex-obsessed. Thankfully, the novelization just got reprinted, so readers can see for themselves how sexy the 23rd century is without network TV censors.).

The Ilia Probe is V’Ger’s way of communicating with the human “infestations” plaguing the Enterprise and her interactions with Decker draw out the real Ilia’s personality for brief moments—it’s duplication process was too effective. It’s tragic because the viewer sees glimpses of a crew member who clearly touched Decker’s heart, but now buried beneath V’Ger’s programming. The Ilia Probe is an alien conduit that serves to remind the viewer the power of V’Ger, but it’s also the reason Decker sacrifices himself in order to provide it with a surrogate Creator; it’s Decker’s sacrifice that saves the day, not Kirk’s actions as per the TV series. The combination of humanity, Deltan, and a living machine merging to create a new life form is a poignant and exhilarating scene, depicting the emergence of a new life form in effective Star Trek fashion. Kirk gets his command, Spock resolves his inner turmoil, Decker and Ilia can be together, V’Ger evolves, and the Earth is saved without a single phaser beam fired.

Jerry Goldmsith’s score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture is one of the greatest cinematic compositions, and its omission would have weakened the film significantly. Goldsmith’s main title march is dramatic, signalling the start of a grand cosmic adventure with old friends, after a decade of being away. The piece is short, but it personifies the thrill of exploring the unknown, the human desire for knowledge (It’s not surprising Roddenberry would use this piece again as the main theme for Star Trek: The Next Generation). It’s perhaps the most recognizable piece of music in the entire Star Trek canon (Goldsmith would revisit it when scoring Star Trek V, First Contact, Insurrection, and Nemesis). His Klingon music is angry, aggressive, and inhuman, which adds to the worldbuilding—he projects the Klingons as a fearsome warrior race, but one ill-equipped to handle a unfeeling cosmic entity; if a heavily-armed armada can be dispensed with easily, how can the Federation hope to survive? Goldsmith’s use of the blaster beam, an immense electronic instrument, to depict the truly otherworldly aspect of V’Ger is ingenious, adding awe and tension in every scene it’s used. The blaster beam was developed in the early ’70s, but was refined by musician Craig Huxley for the film and its sound is startling—outer space had been illustrated with classical music, but the blaster beam’s music felt like it came from another galaxy, a testament to V’Ger’s long voyage home to Earth. Though the other Star Trek films would use an array of talented composers, none were as impressive as Jerry Goldsmith.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture isn’t the film that most fans cite as their favourite big-screen Star Trek adventure, but it’s the film they need. Despite its glacial pacing and restrained approach, the film is a testament to Gene Roddenberry’s vision of a future in which humanity unites to travel the stars in peace and a nod to the revolutionary science fiction films that came before it. Its epic approach to cosmic storytelling convinced a studio and Hollywood that Star Trek could work on the big screen without the sillier aspects of the TV series, push visual storytelling further along, and make a lot of money. Its success spawned sequels and new generations of fans. It’s a marvelous piece of science fiction cinema, and it’s a shame that another ambitious Star Trek cosmic adventure would never be attempted again. Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s scope wouldn’t be repeated in the sequels, and though the Enterprise crew would continue to explore strange new worlds, it would never seek out new life and civilizations the way they had done in their first cinematic adventure. Course heading, Captain? “Thataway,” Kirk gestures, smiling. After all, the human adventure is just beginning.