Experimental cinema is a strange beast. Often treated as something different to more conventional styles of film, it can feel like a sub-genre that’s drowned in the academic, made impenetrable or unable to be understood without endless amounts of prior knowledge. I studied it for a module doing an undergraduate degree, and have only recently returned to it. A lot of it is difficult to seek out, and I feel like this scarcity adds to the idea of it being a niche among niches. But it doesn’t have to be.

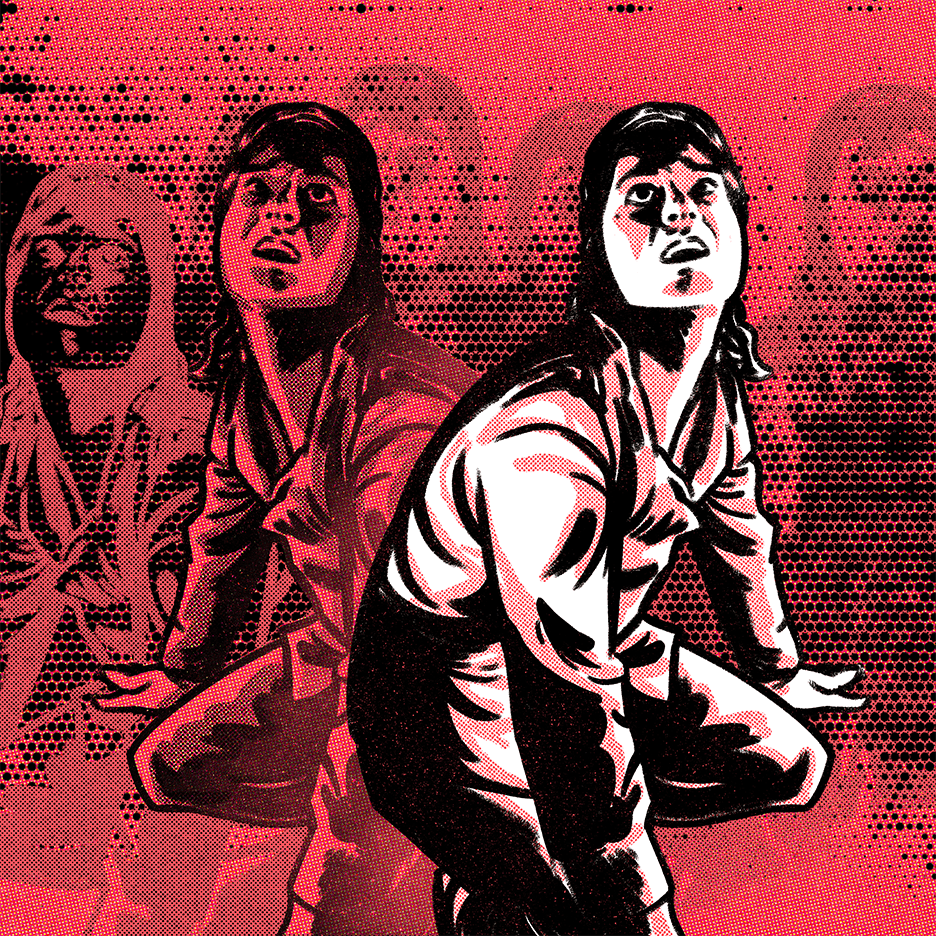

Outer Space (1999), directed by Peter Tscherkassky, is an experimental abstraction made of footage from The Entity (1982). The Entity is about Carla Moran (Barbara Hershey), a woman who finds herself tormented and assaulted in all manners of ways by an invisible demon. This one-line premise also applies to Tscherkassky’s film, although he approaches it in an entirely different way when it comes to form, function, and aesthetics. Tscherkassky strips away everything about the film other than Carla, her house, and The Entity. There’s nothing about her losing her mind here, nothing about parapsychologists. Instead, Outer Space turns Carla’s home into a house of horrors, one where everything is made uncertain; she appears in doubles, in fragments, as if the horror of The Entity is the reflection of Carla herself.

The strange, spectral nature of Carla – although in Tscherkassky’s film she’s unnamed – is rooted in the experimental style of the film. The formal decisions in the film, Carla moving between rooms in a way that seems unreal, the house itself seeming to change at a moment’s notice, amplify the themes. Here, found footage becomes a way into exploring memory and trauma, the idea of a haunted house. One thing that Tscherkassky’s film embraces is the idea that Carla’s house is haunted. What Outer Space does by manipulating footage from The Entity is to twist the perspective; somewhere in the film the idea is always lurking that what we’re actually following is the entity, rather than Carla. As soon as she twists the doorknob to let herself back inside, the camera cuts inside the house, waiting for her to come in.

There’s something strange and voyeuristic about what Tscherkassky presents here. With Carla an unnamed woman rather than the fully-formed character she is in The Entity, the idea of the camera being the entity is reinforced. Who she is doesn’t really matter in Outer Space, instead what matters is the strange refractions and cuts that turn her house into something strange and monstrous. That’s what makes the found-footage – i.e. manipulating pre-existing film footage – of Outer Space so powerful and unnerving, the idea that what we’re watching is in itself abnormal, something uncanny and not-quite-right in the way of a nightmare. With the final minutes of the film taking place in darkness as various images of Carla cut through the black, as if she’s looking at herself, these ideas of the uncanny, the doppelganger, are left lingering.

The last moment of the film is one that manages to tie together the abstraction and confusion that permeates everything that follows in Outer Space. Not knowing what we’re looking at, where the monster is, or if the eye of the camera – and viewer – is in fact the monster, all seems to cohere as, in between these two images of Carla looking at Carla, a third picture of his face appears in the middle between them, as if this was the whole made of two other fragments. Fragmentation is where the power and horror of Outer Space comes from; fragments of something being made surreal, fragments of a house, of a woman, all of them seeming to flicker in and out of reality. Nothing stays stable for long in Outer Space, even images of the corridors in Carla’s house distort and twist, her movements are staccato and uncertain.

This uncertainty is what lets Outer Space turn an invisible Entity – the question of whether or not The Entity exists is a pressing point in the original film – into something physical, and what allows it to at once exist inside and outside of Carla. There are brief moments of dialogue, but, in the way of a nightmare, they aren’t fully formed sentences; just a few words repeated, tripping over themselves as everything else gets stuck in the throat. “What was… what was…” The question of what is never answered in full; it wouldn’t make sense for Outer Space to give a meaningful sense of resolution. Instead, it leaves us with the same pieces that it started with: a woman, a house, and a monster. But once the film is over, the idea of what these pieces are, and how they interact with each other, has been fundamentally changed.

This found-footage haunted house ends on a fragment: a fragment of a room, a fragment of a woman. Fragments imply a broken a whole, and what Outer Space does is challenge us to think about how they might fit together. After all, the film itself breaks down and reassembles The Entity. It seems only right that it ends on the unanswered question of if the film’s final image – Carla in a room, acting like a strange streak of light among the darkness – is itself an act of reconstruction, or if this is the last we’ll see of her before she’s lost forever.

Editor’s note: Tscherkassky’s Outer Space is a short film available to watch in its entirety on YouTube. As it is an obscure experimental film, we thought it would benefit our readers to embed the video here. Please enjoy.