Twice in the course of The Beach Bum, Matthew McConaughey’s greasy itinerant poet-drunk, known only as Moondog, recites his piece “The Beautiful Poem” – once at the beginning, to the weeknight crowd at a beachside dive bar, and once near the end, at his Pulitzer Prize acceptance speech:

I go to bed in Havana thinking

about you.

Pissing a few moments ago

I looked down at my penis

affectionately.

Knowing it has been inside you

twice today makes me feel

beautiful.

This is the only original work of Moondog’s we’re exposed to in the whole movie. And it’s not his. “The Beautiful Poem” was written by Richard Brautigan in 1968 (with only “Havana” subbed in for “Los Angeles”). Elsewhere in the movie he admits to plagiarizing a D.H. Lawrence poem to win a writing contest in high school, but the movie gives us no hint that this particular poem is stolen, and no one shows the slightest sign of suspicion about “The Beautiful Poem,” least of all the attendees at the big gala for Moondog’s Nobel Prize for Literature, the very people you’d expect to catch a thing like that.

This little factoid may seem a bit inconsequential, the type of thing you might read in a Screenrant-like clickbait listicle, but I would argue that it completely changes the tone of the movie. The Beach Bum met with mixed reviews on its release because critics had trouble deciphering how exactly we ought to feel about Moondog. Is he a wounded soul muddling about in the world as best he can? A figure of bumbling fun? A fundamentally selfish taker? The knowledge that this poem, the audience’s only window into Moondog’s lauded literary talent, is actually not his, provides a handy skeleton key. It makes things clear how we’re supposed to view Moondog – but it also tells us that The Beach Bum isn’t really about Moondog at all.

What is it about, then? To answer that, I’d like to dip into the dreaded Discourse for a minute. Apologies.

A lot of feathers were ruffled recently by an essay published in T: The New York Times Style Magazine, under the title “Where Have All The Artist-Addicts Gone?” I didn’t find the essay quite as tasteless as the title promised at first glance, but it’s still no one’s idea of a good bit of writing. It seemed to me to be a dryly historical, padded-out afterthought to a title optimized to generate maximal hate-clicks. The bulk of the essay is just a collection of anecdotes about writers who earned their place in literary history either in spite of, or because of, personal demons that they self-medicated with drugs and alcohol: beginning with Poe, continuing through Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Cheever, Burroughs, all the usual suspects. Then the article segues into the not-particularly-astute observation that that sort of thing doesn’t seem so glamorous nowadays, and it may even be frowned upon for a writer to behave like that. To the extent that the essay even has a thesis, or any kind of claim to make, it’s that “The compulsion for everything to be civil and inoffensive is now reflected in our curious relationship to drugs and alcohol…[o]ur culture now is one in which artists are less troubled geniuses than they are public figures, generally expected to respond uncontroversially on their various platforms to whatever the news cycle might bring.”

There are a lot of ways this piece fails. The writer, M.H. Miller, puts forth a question right there in the title, and then treats it as more of a rhetorical exercise than something that can be seriously investigated and answered. He doesn’t seriously question whether writers, “great” or otherwise, are really more prone to addiction or mental illness than others; the closest he comes is citing a laughably unrepresentative survey of one year’s worth of candidates at the Iowa Writers Workshop. He doesn’t ask whether the experience of the great celebrated Artist-Addicts are representative of addict artists as a whole. He doesn’t bother to note that the emergence of the “artist-addict” archetype didn’t come about until industrial capitalism and the corresponding rise of the “creative” person as both an economic and a social category. This is intensely frustrating because if he had taken the time to find out where this archetype came from, it would quickly become clear where it’s going. He doesn’t see fit to talk about the professionalization of the arts, the vast decline in pay for the average working writer, the near-impossibility for a writer to support oneself by their work alone without some sort of day job, usually in academia or publishing, affording little room for drinking binges, scandals, and professional bridge-burning. The opioid epidemic gets a scant few throwaway lines, when surely it is relevant to this conversation that legitimate doctors are now writing grandmothers prescriptions for smack ten times stronger than anything Burroughs ever shot up in his life.

Each of these failures to investigate is forgivable, at least individually. There’s one, however, that isn’t: why does the Artist-Addict fascinate us so? Why do we speak of their lives in hushed tones, even as we cluck our tongues at the specifics? Mr. Miller does broach the issue, briefly, near the end, and then skitters away like a spider from the candle. He rounds out the article with an unconvincing anecdote about how he wanted to understand the life of the Artist-Addict, so he could avoid the fate of John Berryman, the famous poet who drank himself off a bridge 50 years ago this year, and that of any number of Artist-Addicts to whom he feels a spiritual kinship. The truth, I believe, you can intuit from watching The Beach Bum.

When we meet Moondog, he’s on an extended debauch in the Florida Keys, living on a houseboat, drinking and toking at all hours, living the life of a celebrated local eccentric, adored by a sun-soaked public that generally considers him over the hill artistically, but a fun guy to hang out with nonetheless. He does nothing, womanizes freely, and leaves spilled drinks and the occasional pool of blood from a drunken mishap for his long-suffering housekeeper to clean up.

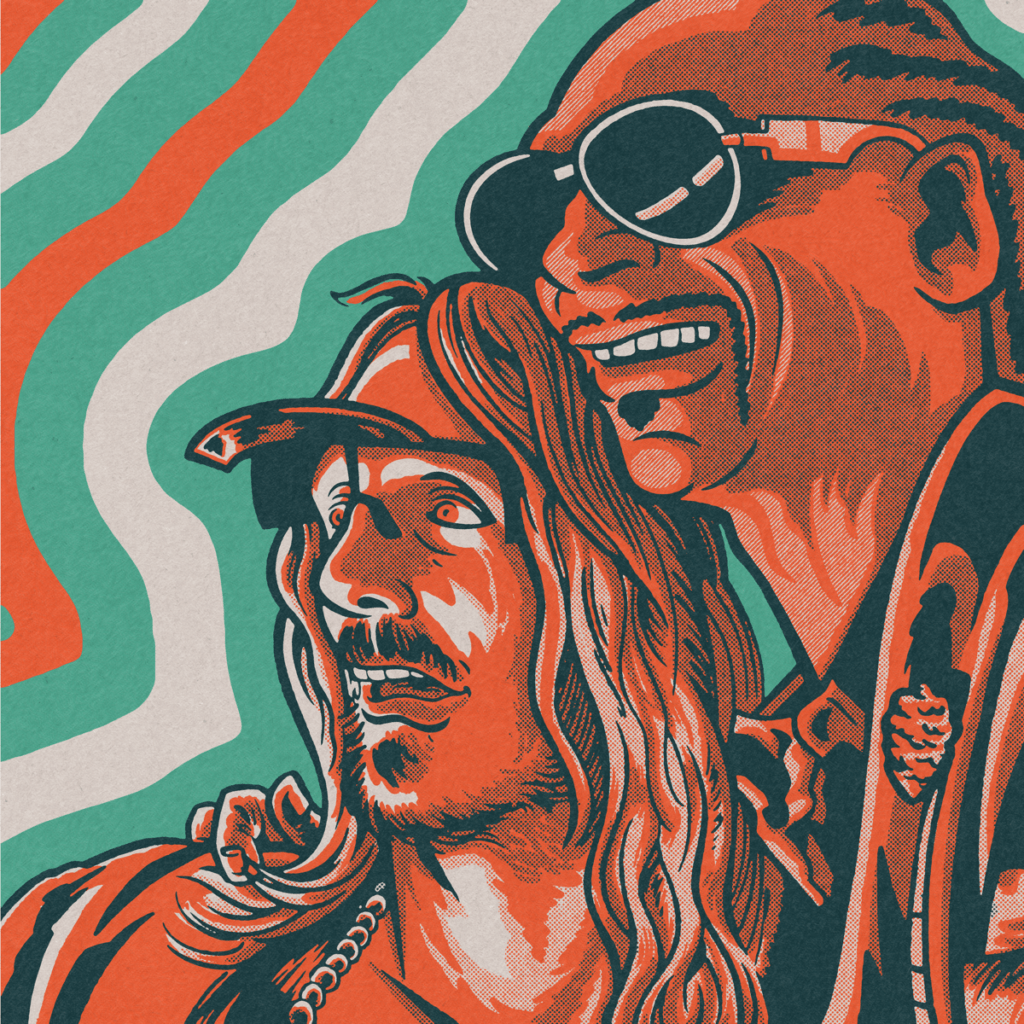

Moondog is pulled out of Margaritaville by his lovingly indulgent and obscenely wealthy wife Minnie (Isla Fisher), who calls to summon him back to their Miami Beach mansion for their daughter’s wedding. Moondog shows up loaded, embarrasses his daughter, insults his new son-in-law mercilessly, and accidentally discovers that Minnie is having an affair with his best friend, R&B singer Lingerie (Snoop Dogg). This is the first consequence of his actions Moondog has ever encountered, and he responds by leaving the wedding and going bar crawling. Minnie tracks him down, and they enjoy a drunken and diverting evening before her violent death in a car wreck.

Henceforth comes the second consequence Moondog has ever encountered: his Minnie, being a bit more astute than she initially seemed, has decreed in her will that Moondog will not get any of her money until he gets off his hinder and finishes the Great American Novel he’s been chipping away at for years. After being rebuffed for money by his daughter, he rounds up a gang of homeless fruitcakes to smash up his wife’s mansion. He gets sentenced to rehab, breaks out with the help of an inhalant-addicted pyromaniac named Flicker (Zac Efron), and embarks on a shaggy-dog series of comic misadventures.

The life of Moondog in The Beach Bum is the ideal form of the Artist-Addict as outlined in “Where Have All The Artist-Addicts Gone?” Everybody seems to love him. Everyone makes endless allowances for him in light of his “genius” and his easygoing party-animal nature. There doesn’t seem to be anything he can do to get the people in his life to stop tolerating him. Even while making half-hearted entreaties to get a move on that novel, his agent (Jonah Hill) treats him to free drugs and golf games. Even in the middle of denying him money, his daughter expresses faith that he’ll finish his novel, and when her husband gets annoyed at his constant belittlement, she belittles him right back and calls her father a genius. There seems no limit to Moondog’s blessings. He stumbles Candide-like through one disaster after another from which he miraculously escapes unscathed every single time. And when all the adventuring is done, Moondog sits down, having learned a whole lot of not-a-lot, and somehow finds inspiration to finish his novel, which is an immediate hit that solidifies his literary reputation and wins back all the respect of his family and the literary world.

It all seems more than a little fantastic, an impression only heightened by The Beach Bum’s aesthetic: sun-splashed tropical landscapes, shimmering ocean views, idyllic bars and beach resorts, neon-drenched night parties. Stylistic choices reinforce this: scenes regularly slip into another with a couple of quick flashbacks and flash-forwards, with the same conversation confusedly playing out across shots that take place in different locations and times, evoking the fluid temporal logic of the dream (or the hazy time perception of the perpetually drugged-out). Moondog himself is a protean, Loki-esque figure, often appearing with the Florida sun catching his bottle-blonde hair and making it shine like a halo, or at night, with harsh neon lighting washing his features into an unrecognizable smear, and McConaughey leans into the inconstancy, pulling his face into a hundred unsettling variations of a stoner grin. He treats his own life like a not-particularly-lucid dream, obeying his every impulse, stealing beers out of coolers, stealing fishing rods just cause he feels like fishing, having a series of fortuitous run-ins with people he knows and jumping into half-baked adventures with them, with the disregard for consequences that only fantasy or sociopathy can provide.

Yes, by almost any measure Moondog is a very bad person, a fact The Beach Bum makes very little effort to hide from us or to justify. And this is another important element of the Artist-Addict mythos. In “Where Have All The Artist-Addicts Gone?” Miller writes “These days, it’s incredible to think about the lengths we used to go to in order to forgive artists for being bad people. Ours was once a culture that awarded Norman Mailer — an inconsistent writer — not one but two Pulitzer Prizes, and that was after he nearly killed his second wife in a drunken assault … Allen Ginsberg once said of Burroughs that he didn’t become a serious writer until after he shot and killed his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer, in a drunken attempt at performing a William Tell act.” To this, Miller can only baldly respond: “These comments haven’t aged well.” But to Miller’s thinking, there’s an evil greater than tolerating these crimes, and that would be to let our fear of repeating them turn artists into dull, mediocre nobodies. These days, Miller writes, “Everything and everybody…must be bland and inoffensive, or one runs the risk of that legendary cancellation in the sky, a myth that has overtaken the Hemingway-like figure, the high-functioning addict whose great work was fueled by liquor and drugs”.

This cancellation boogeyman, that feared spectre of the New York Times opinion pages, troubles Moondog not one whit. His venality is precisely cut to fit the contours of the romantic outlaw, his every misdeed falling within the realm of the human and the forgivable. He doesn’t beat women, he isn’t a sex pest, he doesn’t have any problematic political axes to grind; he does womanize, but you can’t call him toxically masculine because he cross-dresses. Terrible misfortunes are constantly befalling the people in Moondog’s orbit, but he’s only abstractly responsible for any of it, with enough distance between him and true culpability that it seems worth a chuckle and not a scold. Sure, Minnie may have been killed while they were out drinking, but she was the one driving, not him. Sure, Flicker may have robbed a man on a motorized cart for beer money, but it wasn’t Moondog’s idea, and he halfheartedly tried to stop him. Sure, Moondog’s friend Captain Wack (Martin Lawrence) may have gotten his foot bitten off by sharks while giving (what he thought was) a dolphin tour, but Moondog tried to warn him about the sharks. Only in the very last scene of the movie does Moondog veer close to a cancellable offense, when he collects Minnie’s inheritance in cash on a boat and semi-accidentally blows it up for a crowd of cheering spectators, forgetting that an adorable kitten he’d picked up earlier in the movie is on the boat. The camera lingers on the cat just before the explosion, ensuring that you feel a sick sensation in the back of your throat until the next scene, where Moondog has somehow gotten the cat off the boat and breathlessly laughs, “That was a close one, buddy!”

The only people Moondog directly mistreats are those who are below him on the social ladder: the housekeeper who has to go above her pay grade to patch him up after a drunken fall, the butlers who have to stand awkwardly by while he goes down on his wife in a beach chair, the short-order cooks who can’t do their jobs because he’s having sex with a beach floozy by the grill. Despite his man-of-the-people pretensions, Moondog really likes to do things like this. At one point Moondog’s agent confesses: “You know what I always loved about being rich? You can be horrible to people, and they just have to take it.” Moondog laughs in full-throated agreement.

So, to recap: Moondog lives a life glamorous beyond both his means and his dessert, and yet his comeuppance never comes up. He is an addict, but only to booze and weed and coke; not to any hard drugs, which would veer the whole story into depressing territory. He’s a bad person, but not in a way that might get his novel removed from any school curriculums later on. He can treat anybody however the hell he feels like, and the people who matter love him for it, and the people who don’t can’t say boo about it. And at the end of the story, having regained his gigantic pile of unearned wealth, he sets fire to it all, not because he doesn’t want it anymore, but because he’s realized he doesn’t need it: things are always going to work out for him.

In case it’s not clear yet, I’m saying that Moondog’s whole life, and the life of the great Artist-Addict, is a fantasy concocted by the educated, domesticated middle-class types who overwhelmingly write, market, and read literary fiction. Everything about him reeks of bourgeois wish-fulfillment: his crass manners, his hedonism, his indifference to social convention, his itinerant lifestyle, and above all his massive financial and critical success without having any formal education or paying any mind to publishing industry politics. Moondog alone can live like it’s still the glamorous midcentury when writers were rockstars and a single Harper’s byline paid three months’ rent. He alone can be as boorish and politically incorrect as he likes without the Cancel Monster pouncing on him. And he alone can act like being a writer puts you far enough above anybody else to justify treating service industry employees like furniture. The art of the movie has been described as putting a dream on a screen for others to see, and this particular dream springs from the id of a million struggling writers who read Papa Hemingway and dream of indulging self-destructive and antisocial impulses under the banner of their art.

But the dream of The Beach Bum is also a lucid one. Moondog’s many sins are all expiated by his vaunted literary genius, the only example of which we ever see is “The Beautiful Poem.” The knowledge that it was plagiarized breaks the spell the rest of the movie casts. (The poem’s original author, Richard Brautigan, was a classic Artist-Addict and lived a life very similar to Moondog’s in many respects, but unlike Moondog, when his star faded, he committed suicide at 49.) This all-excusing genius is a lie. Moondog claims he needs to live the life he does to get the literary juices flowing, but when it’s time to produce he has to resort to thieving. Nor is he a deep enough thinker, or a sensitive enough person, to have any personal demons he needs to chase away with the boozing and whoring, as we’re told all the great Artist-Addicts do. He lives the life he does because people want him to.

Moondog didn’t invent the Artist-Addict. Our society, our culture, invented the Artist-Addict as a product of middle America’s frustrations and anxieties. We romanticized these figures, we enabled their behavior, and we wrung their lives for every drop of vicarious fantasy we could squeeze. When Moondog reads “The Beautiful Poem,” The Beach Bum reveals itself as a savage satire of a literary establishment that sustains itself by peddling adolescent hedonism fantasies spun out of real people’s painful lives. Moondog sidestepped all that by turning himself into a fantasy. He lives the dream, and we buy it. He’s no genius, just able to exploit his own niche, and in this grubby dog-eat-dog world of ours, no one can blame him for that. ★