In 2016, I went with my mom and my aunt to go see The Turtles play. It was a good time– Iowa’s a good state for that sort of thing. We went to see them at the (in)famous Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake. You may have heard of it: it’s where the music died (Well, if you wanna get technical, it died in a soybean field some miles away.). The Surf is still around, playing host to any number of past-their-prime acts from The Beach Boys to Candlebox (who played one of the last shows there before we entered Covidland). But that’s not the only place to see geezers: we also have very liberal gambling laws, and, as a result, dozens of casinos, each one eager to book acts that will pour sweet nostalgia into the hairy ears of their graying clientele (I saw The Guess Who at the Meskwaki once and got so drunk that I ruptured a vocal cord singing along to “These Eyes.”). And, of course, we have the world-famous Iowa State Fair, the biggest and most State Fair-ish state fair in all the land, which books more Blackfoots, Blue Oyster Cults, and Barenaked Ladieses than you can shake a fried Twinkie at. Yessir, if you want to see a bunch of bands your parents dry-humped to, Iowa’s the place to be!

It was fun seeing The Turtles. Original Turtles members Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman were leading this particular incarnation of the group and they earned their top billing. They’re both incredibly charismatic performers and their decades in the biz gave them both a gift for winding up an audience and lots of stories to do it with. A lot of young musicians would find it appalling to picture themselves coasting on nostalgia fumes like that, but Howard and Mark were taking it in stride–they’re in it for love of the game. If they’d had a couple other hits and a more transformative body of work, they might feel pressure to work a little harder, stay relevant, and prod themselves to make self-conscious, envelope-pushing albums like Bowie or Dylan did in their old age. But they didn’t. They wrote one song catchy enough to make aliens monitoring our radio transmissions involuntarily vibe out, and with that one song they made enough money to just kind of fart around for the rest of their lives–I find that inspiring. The whole rock star archetype is almost as played out as it is a pain to try to live up to, and I’m glad that the Turtles didn’t try.

Part of the reason that we have such ridiculous expectations of our aging rock stars is that Hollywood loves to glamorize their stories–they can’t get enough of this crap. They put out new iterations of the same story every dang year and at this point it’s practically just shuffling names, faces, and costumes around. The genre conventions of the biopic are some of the most idiotic and ironclad of any genre, the music biopic, doubly so. The beats of these stories are etched into our brains: born into poverty, childhood tragedy, going from rags to riches, drug problems, paternity suits, brushes with the law, and a big flameout followed by the subject discovering what’s really important. Like some sci-fi translator who can hear a sentence and reconstruct a whole language from it, I can usually watch any five minutes of a music biopic and predict all the story beats with at least 90 percent accuracy.

Of course, it’s no great surprise that all the movies in a certain genre tend to have similar plots–that’s one of the definitions of a genre. Working effectively within a genre is all about finding a new spin on a formula and a lot of music biopics don’t bother–they rely on the audience’s familiarity with the subject to do the heavy lifting for the story, padding it out by dazzling us with expensive period clothes, wigs, cars, etc.. The person in the lead role is always doing lots of cringe-worthy, actorly tricks trying to “inhabit” the character (the Oscars eat this stuff up), as are the parade of celebrity bit parts these movies always have to have so that audiences can feel rewarded for being able to say “Hey that’s Ozzy, cool!”

These tropes pop up so much because biopics aren’t about finding something new to say about famous musicians, but pleasing crowds by giving them things they recognize– fanservice is paramount. Rarely do you see anything truly revelatory, something their life story explains about how the world works, or anything that would make audiences still care if it were about someone they didn’t already know and love. You cannot tell me that if you made Bohemian Rhapsody, but switched the main character to an entirely fictional character, that anyone would care (In fact, I can prove it–the movie Rock Star fictionalized the story of Tim “Ripper” Owens becoming the new singer for Judas Priest after Rob Halford left and guess what? No one cared.). It is just not a style of filmmaking I find interesting.

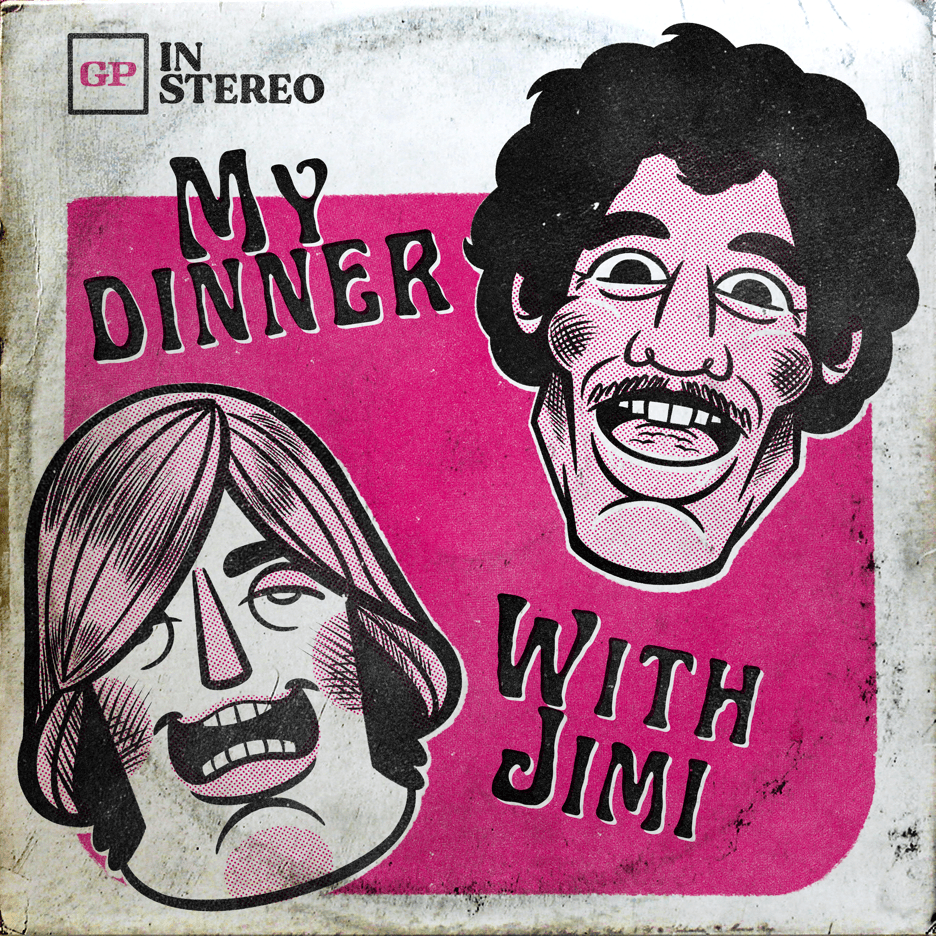

But I do think the movie My Dinner With Jimi, self-financed by ex-Turtle Howard Kaylan, is interesting and it isn’t because it’s a particularly well-done movie. Kaylan wrote and produced it on a shoestring budget with a cast of unknowns (there are a few exceptions, like George Wendt and the guy who played Booger in Revenge of the Nerds)–and only one public screening at the Toronto Film Festival in 2003. It doesn’t have the sort of towering hagiographic ambitions of a typical biopic: watching it, you don’t get the sense that Howard Kaylan even meant for a lot of people to see it. The whole thing was a vanity project, something fun he thought he could do. And that’s what makes it so refreshing.

The largely-plotless narrative of My Dinner With Jimi begins in LA in 1966. Howard Kaylan, 19-years old and already having a hit song on the radio with “Happy Together,” is on top of the world. We see stock footage of LA in the swinging ’60s–beach parties, the Sunset Strip, Whiskey-A-Go-Go, Canter’s Deli–and we’re introduced to a lot of huge figures that The Turtles rubbed elbows with, including Frank Zappa, Jim Morrison, and Mama Cass; Kaylan talks to these guys as equals, trading concert reviews with them (newspapers used to have those!). This part of the movie is hard to interpret because it seems to desperately want its own shot at all the biopic tropes I spent the first thousand words of this essay complaining about. But as I said, part of the reason they pop up so often is because our familiarity with the musician in question is what makes them fit together onscreen. The difference here is that lots of people are familiar with the minutiae of, say, Freddie Mercury’s life. How so for the Turtles? I’m sure there are three or four hardcore Turtleheads nodding approvingly, but for the more casual viewer it sure just sounds like a boomer telling big-fish stories about all the cool stuff he did and all the cool people he met.

Is Howard Kaylan trying to put an ironic spin on his story, or does he genuinely believe that his own life is worthy of that kind of mythmaking? The movie never makes it clear: scenes are idealized but not starry-eyed, shot in a way that’s both low-key and boastful. Howard depicts himself both as an overwhelmed idiot kid and an impossibly-cool, rock-star prodigy. We’re never exactly sure how seriously he’s taking himself–the only thing for certain is that he’s having a blast.

There’s trouble in paradise, however–Kaylan and his guitarist Mark Volman get their draft cards. Scared out of his wits and not wanting to leave his newfound lifestyle behind, Kaylan contacts his cousin, Herb Cohen, who manages Frank Zappa (Kaylan and Mark Volman would later join the Mothers of Invention as “Flo & Eddie” after contractual hijinks prevented them from performing as The Turtles.). He’s clearly thinking Cohen can bribe someone or call in a political favor. Instead, Cohen gives him some more practical advice–make the Army not want to draft you: “If you have drugs, take them. If you feel like taking a shower, don’t. If your body craves rest, deny it.” The goal is to appear like an insane disheveled bum whom no military would trust with a paper clip, let alone a gun. The Turtles all take his advice and stay up for several days on a drug binge before reporting to their draft board. They flunk all the written tests intentionally, do the opposite of everything the proctors ask, and imply that they are sexual deviants. These scenes of debauchery have subversive humor, which comes from a band that most of us associate with toothpaste commercials guzzling liquor-and-reds smoothies and making goo-goo eyes at a military policeman; it’s also a great antidote to a lot of the self-serious depictions of sex’n’drugs’n’crime in the typical music biopic. The depiction of rock’n’roll excess in these movies follows a depressingly predictable pattern: first as a wide-eyed entry into a new, more colorful world, a glamorized cri de coeur of youthful freedom and rebelliousness, then as a black whirlpool sucking the artist inexorably into the second-act rock bottom. One or the other (or frequently both) happens in La Bamba, The Doors, Ray, Walk the Line, La Vie En Rose, All Eyez On Me, The Dirt, and too many other biopics to name. But neither happens in My Dinner With Jimi. Howard Kaylan is an old fart, so he certainly doesn’t want to encourage drug use, but he’s not making a D.A.R.E. PSA either–he’s laying out the facts about himself as a young dummy doing what young dummies have done since time immemorial.

The scam works like a charm. Thanks to Herb Cohen, the Turtles are free to go to London the next year on an English tour and meet all of their personal idols. More name-dropping ensues: they go to Donovan’s apartment and smoke hash with him and Graham Nash, and listen to a reel-to-reel copy of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which is set to debut the next day. Amazed at the musical and technical accomplishment therein, the band hits the pubs, still talking about the album. They run into the Moody Blues, Eric Clapton, Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones, and, later, of course, The Beatles. Unfortunately, the Beatles do not live up to the band’s expectations. John, in particular, is portrayed as a nasty, cruel sort, prone to drunkenly mocking the less-famous Turtles, leading guitarist Jim Tucker to leave the bar (and the music industry altogether) in disgrace. After this ignominious encounter, the band trundles home, all except the heartsick Kaylan. Brian Jones chases Kaylan outside to tell him someone wants to meet him. Another up-and-comer, someone who has some music of his own coming out soon: an American guitar prodigy named Jimi Hendrix.

Supposedly Kaylan hadn’t known who Jimi Hendrix was before running into him at this bar, but because this is Howard Kaylan writing his own story, Hendrix already knows who he is, having listened to some Turtles records, and he and Hendrix end up getting along splendidly. Jimi orders Kaylan dinner and several drinks right off the bat, and they have a long chat well into the night. They talk about Kaylan’s jitters about his upcoming marriage. Jimi reassures him. They talk about music. Jimi tells Kaylan he admires how well he can sing, wishes he could too – his guitar technique, he says, is his way of recreating the music that he wishes he could do with his voice. Jimi orders more drinks, produces a spliff, lights it up, and the talk turns philosophical.

Most music biopics have a scene where someone speechifies dramatically about the deeper meaning or philosophy of the subject’s music. These scenes are usually pretty ponderous, a victim of the aforementioned tendency to compress and simplify musicians’ lives to fit the demands of a narrative. In Selena, Selena’s dad Edward James Olmos has such a speech about how her music is an expression of her Mexican-American identity. In Walk the Line, Joaquin Phoenix’s Johnny Cash basically sums up the lyrics to “The Man in Black” in dialogue, talking about his hard-bitten music as a testament to and protest of injustice (never mind that the majority of Cash’s output is gospel and novelty songs). In Bohemian Rhapsody, Rami Malek, as Freddie Mercury, spins a whole web of platitudinous garbage about how Queen is music for misfits or some crap like that (I really do not care for Bohemian Rhapsody).

It seems like this moment with Jimi at the dinner table is going to contain one of these scenes. Jimi explains to the white-bread Kaylan his theory of “soul” as it relates to his album’s title, Are You Experienced? He asks Kaylan how he finds fame, and the abashed Kaylan admits he thought there would be some big revelation along the way that would help him fit into this life, but so far he’s just as confused as ever. He talks about the high he gets performing in front of audiences, the rush, as he puts it, “They’ll never know that we’re the damn audience and they’re the show.” Jimi concurs: “The higher they get, the higher they make me, and the better I play.” This whole lofty discussion, however, comes to an abrupt end when Kaylan, strung out from overly-strong drinks and too many tokes, vomits his spinach omelette all over Jimi’s crushed-velvet suit. At that moment, the wisdom-spouting Hendrix turns into a petty rich boy, moaning and pitching a fit about the cleaning bill. The next morning, as Kaylan nurses his hangover, he muses to himself about all the rock stars he met last night, accidentally articulating the real moral of the story: “It was the funniest thing. They weren’t gods. They were just like us.” There’s some mop-up, but that’s pretty much the end of the movie. There’s really no way to verify the veracity of any of this: on the surface, the chronology checks out. There’s nothing anyone can point to and definitively say it didn’t happen–the closest would be the encounter with John Lennon, who, according to some people who were at that pub, was too drunk to string two words together that night, much less craft a devastating insult to end someone’s music career. And yet it rings false because of the self-congratulatory nature of Kaylan’s narrative–he always meets exactly the right people, on whom he makes exactly the right impression. They shower him with praise, assuring him that he has artistry, insight, and coolness equal to theirs–it all plays like the comfortable fantasies of a Hollywood has-been.

These are the kind of plot mechanics that would grate on the nerves in another biopic, not that I necessarily believe that a biopic has to be truthful to be good. These aren’t documentaries here–veracity isn’t their goal. In some ways I prefer when a biopic has transparent BS in it, as Beyond the Sea did, and as The Dirt flirted with doing, but ultimately chickened out. But this, too, can grate because too much 4th-wall breaking and too much meta nudge-nudge wink-wink run the risk of feeling cutesy and insincere: “Look how big an idiot you are for taking this artist’s life story seriously.” My Dinner With Jimi finds a nice balance straight down the middle–Kaylan isn’t telling his story with a sneer. Even when he’s spouting BS, it’s sincere BS, committed BS. His natural talent as a tale-spinner and a crowd-pleaser means he knows where to trowel it on and where to leave it bare. At no point was I watching the movie and thinking, “Jeez, aren’t you laying it on a little thick, there?” Kaylan is doing pure boomer shtick–maybe he gets high on his own supply occasionally, but we’re inclined to forgive him because he has no delusions of being the voice of a generation. He had a comfortable life hobnobbing with celebs, but never reaching those steely heights himself, and now he just wants to sit back and play in his memories.

The film’s short timeline helps eliminate one of the most egregious aspects of the biopic rigmarole: a human being’s life, no matter how famous, fits into a normal Hollywood three-act structure like a porcupine fits into a briefcase. To turn a life into something filmable, you’re obligated to perform some tricks: you can compress the timeline in certain places and stretch it in others. You can amalgamate several people into a single character, or invent a person entirely. You can invent scenes that never really happened in order to get a clean story beat. There’s nothing inherently wrong with any of these practices, but there are plenty of wrong ways to do them. Too often they result in scenes that are stilted and contrived, and dialogue that’s blithe expository–bare story structure with zero ornamentation. Are we really supposed to believe that Elton John (as depicted in Rocketman) called his mother while running late to a show, in full costume, to come out to her, which she already knew, and during the same conversation she told him, “No one will ever love you properly”? There are, like, seven different ways that doesn’t make sense.

A lot of biopics on the artsier end of the spectrum will remedy this problem by focusing their narrative on a smaller window of time, giving the script a little breathing room, allowing for more naturalistic interactions and conversations. A lot of times the period is a relatively uneventful one–see Control (about Ian Curtis of Joy Division), All Is By My Side (Jimi Hendrix), and Miles Ahead (Miles Davis)–but even those films can’t resist the temptation of a heart-tugging flashback or two. My Dinner With Jimi wouldn’t dream of it. Partially, this is out of necessity, as Howard Kaylan’s childhood and upbringing was, as far as I can determine, totally unremarkable. We get the sense that Kaylan isn’t the tortured-artist type–he loves being famous too much to dwell on anything that happened before. And of course, you have to consider that Kaylan’s unusually close relationship to the movie is a factor: old men love to spin tall tales about the past, but none of them likes it when you point it out.

The duties behind the camera are handled by Andrew Fishman, best known as the director for the cult comedy Tapeheads and a lot of music videos. Like Kaylan’s script, Fishman’s direction walks a fine line between satirizing the antics of self-indulgent rock legends and celebrating them. No stranger to revisionist nostalgia (he directed the much-maligned movie version of the ’50s cop sitcom, Car 54, Where Are You?), Fishman uses his music-video skills to shoot splashy, kinetic takes that have an almost absurdist touch. In some scenes, he settles into a jerky, underlit, almost verité style that wants to lend credence to the movie’s supposed veracity. Some shots look cheap as hell because they are in fact cheap as hell–Fishman wants to communicate the grubby reality behind the glitzy sheen of the rock’n’roll myth. At least one shot, the Turtles’ appearance on the Smothers Brothers, looks hilarious–the set so cheap, the band’s gestures so hammy–-you think it has to be a joke until you look up that clip on YouTube and find out that nope, it actually looked like that; if anything the set in the movie looks a little bit better.

Kaylan’s avatar on film, Justin Henry, is another peaked-early type: he’s best known for playing the little kid in Kramer vs. Kramer, netting himself the youngest-ever Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Kaylan could have picked Henry because of this, but then again, he could’ve picked him because he worked cheap. In either case, it adds another subtle layer of surrealism to see a guy who is clearly in his 30s playing a gawky 19-year-old getting his first taste of fame, especially since he plays the part while wearing what has to be the fakest wig and the fakest-looking sideburns I’ve ever seen. Did Kaylan mean for this to happen? Was he putting a too-old actor in kids’ clothes to make some sort of point about the foolishness of nostalgia? Was he trying to represent his older self looking back at his youth? In the end, you don’t know. It’s tough to judge these things because of the high degree of amateurism in the production, but that’s entirely a good thing in this case, believe me–tonal confusion suits it. The movie achieves the impossible: it’s a goofy, irreverent biopic with not one ounce of overt irony. In the end, My Dinner With Jimi works perfectly well as both apotheosis and parody of the music biopic.