By now you’re assuredly at least somewhat familiar with the term “incel.” An abbreviation of “involuntarily celibate,” the word refers to a group of people – mostly young, mostly male – united by extreme difficulty in finding sexual and romantic partners.

If you keep up with the news, you’ve probably read this word more than you’d have liked to. Last month, Canada prosecuted a young man who attacked a Toronto massage parlor with a machete as a domestic terrorist – the first time such a label has ever been applied to an incel-involved attack. Only a month before that, Armando Hernandez Jr. shot up an Arizona shopping mall, sending three people to the hospital; Hernandez identified as an incel and said he was targeting couples. Alek Minassian killed ten people with a van in 2018 for similar reasons. In the same year, Scott Beierle attacked a Florida yoga studio after uploading a series of incel-related YouTube videos. Chris Harper-Mercer shot up an Oregon college campus in 2015, attributing his inspiration to the patron saint of inceldom Elliot Rodger, whose 2014 shooting spree and accompanying manifesto established inceldom as a violent terror threat.

What kind of man, you may ask, would kill strangers simply out of sexual frustration? Well, the short answer is, they don’t. After all, there have always been romantically unlucky people out there. But the rise of the Internet has facilitated the creation of dark online echo chambers – blogs, forums, chat apps – where huge numbers of sexually frustrated men could gather to share stories, vent their feelings, indulge each other’s misogynistic fantasies, and eventually radicalize one another.

In the course of my research for this piece, I gave these places a look. I don’t recommend it. First off, it’s hard to find up-to-date examples of incel discourse because their subreddits keep getting banned for inciting violence, and I fear signing up for an incel forum would put me on some kind of list. Second, it’s every bit as bad as you would expect. I don’t claim to know what these message boards were like in the early days, but any pretense of being a “support group” went out the window a long time ago in favor of high-octane woman-hating. Lots of “women deserve rape.” Lots of “women are literally Hitler” (that’s a direct quote). Lots of dehumanizing terms for women like “femoids,” often shortened to “foids,” and “roasties,” a term which evokes the distended, roast-beef-like labia women supposedly get from having so much promiscuous sex. They’re blithely incoherent, pursuing their hatred wherever it goes, swinging back and forth between “women hate sex” and “women’s horniness turns them into dumb animals”; between “women are of subhuman intelligence” and “women are capable of complex diabolical scheming.” It’s bad, man.

It took scholars with more stomach than I to sift through all this bile and piece together a semi-coherent ideology capable of inspiring terrorist acts. This ideology – the acceptance of which is denoted by the term “taking the red pill” – claims that women are naturally hypergamous, i.e. always looking to trade up their sexual partners. In past ages, we fought this tendency by building patriarchal institutions that suppressed and guided women’s sexuality, ensuring that men and women of relatively equal status found each other, got married, and stayed married. But thanks to some crazy BS called “feminism,” women are too sexually liberated to submit to wise male guidance, and instead spend all their time throwing themselves at super-hot playboys (“Chads,” in incel parlance), leaving men on the bottom rungs of the looks ladder doomed to a sexless, loveless life.

When incels commit terrorism, it’s this system they’re trying to fight. Their ultimate political goals are nebulous and vary from person to person, but they all include some form of “enforced monogamy” that will restore equity to the “sexual marketplace.”

The incel phenomenon has always been an online one, but you may be surprised to learn that it hasn’t always been a gendered one. The first “incel,” in fact, was a woman. In 1997, a Canadian woman known to history as Alana, who’d suffered from extreme difficulty in her dating life, set up a web forum called Alana’s Involuntary Celibacy Project, for people in similar situations to talk to one another and share support and advice. This forum was gender-inclusive and by all accounts had a fairly even gender ratio in the early days.

Today, of course, men have largely run away with the label “incel.” The main hub of female incel (“femcel”) activity is r/TruFemcels, boasting over 25,000 members. It’s difficult to figure out exactly how many of these “femcels” exist in comparison to male incels, not only because the headline-grabbing violence the latter commit grabs so much more media attention, but because modern incels have had many of their subreddits and other forums shut down in the wake of incel terror panic and have been pushed to the dark web.

With all these highly publicized crimes pushing the media into a full-blown moral panic, one wonders why incels aren’t a bigger cultural boogeyman by now. Incels are the single fastest-growing domestic terror threat. If you live in the U.S. or Canada, you’re more likely to be killed by an incel than by a radical Islamist, yet the latter still show up in plenty of movies and shows. In fact, aside from a few police procedurals doing some “ripped from the headlines” episodes, incels have barely permeated the cultural imagination at all, an unforgivable oversight when even Slenderman has his own movie.

Admittedly, that may not be a fair example. Movies are typically the last form of pop culture to reflect new social trends simply because they take so long to make. Incels themselves – avid pop culture junkies as they tend to be – have retroactively enshrined a handful of movies as a modern incel canon. These movies’ protagonists are men, typically loners, alienated, victims of cruel and uncaring treatment which pushes them to the edge. Sometimes the incel angle is obvious (as in Taxi Driver) and sometimes less so (Joker).

But perhaps the most enduring and influential of these movies is 1999’s Fight Club. Fight Club features a meek, lonely man who feels unfulfilled and self-medicates with conspicuous consumption. He hallucinates a man named Tyler Durden, a muscular, reckless alpha male who takes it upon himself to break the Narrator out of his spiritual prison. He sets up “Fight Club” as a means for men to get in better touch with their destructive primal urges, which eventually forms into a terrorist cult called Project Mayhem, devoted to overthrowing a society that he feels stunts men with fake pleasures and empty promises.

The parallels between the movie and the modern incel movement are easy to spot. The most obvious one is the fatal conflict that arises between the unnamed protagonist and Tyler over Marla, a woman the former pines over and goes to great lengths to win, only for Tyler to seduce her effortlessly and then neglect her (that’s what Chads do, after all). Tyler’s beliefs about society mirror the ideology that’s grown up around incels – Tyler tells men that what they perceive as their personal failings are actually the fault of a hostile society. The cultish social structure of Fight Club and of Project Mayhem bears an eerie resemblance to incel communities, with Elliot Roger and other incel heroes receiving the same saintlike reverence paid to Tyler in the movie. (Alek Minassian infamously wrote a post immediately before the Toronto van attack, identifying himself with an army designation and vowing “All Hail Supreme Gentleman Elliot Roger!”)

This de-centering of personal motivation, the focus on the organization as an organ of ideological warfare, helps explain the relative lack of incel narratives in film and elsewhere. There are any number of thrillers and horror movies about violent people motivated by sexual frustration or romantic rejection, but that doesn’t make them “incel movies.” These killers’ motivations are highly personal in a way those of incel terrorists aren’t. A sexually frustrated man seeking retribution from the actual woman or women who rejected him isn’t unheard of by any means, but it’s not a typical part of the incel terror pattern. The defining quality of an act of terrorism is that the people who get injured and die aren’t the actual targets. The targets are everybody else.

And it’s difficult to write a narrative about this kind of thing that hits the emotional notes you would want it to hit. There’s a limit to how compelling you can make a villain who’s not interested in hurting anyone specific. Even in movies about serial killers, i.e. people who kill at random, in order to make a plot happen you usually have to put your protagonist in some kind of scenario which breaks the killer’s ordinary pattern, gets on his bad side somehow, makes things personal. An Elliot Rodger-type figure could no more be a horror villain than an avalanche could.

But Lucky McKee’s 2002 directorial debut, May, does exactly this. Or maybe not. If it’s possible to look back and note Fight Club’s prescience where incels are concerned, then we can surely do the same with May’s treatment of femcels. McKee’s choice of a woman as his protagonist is a neat way of squaring the circle. Women, for the most part, don’t process involuntary celibacy in the same way that men do, and examining the difference makes May not only a cleverer social statement but a more incisive examination into the rot at the core of an incel’s soul.

The eponymous protagonist of May is a woman in her twenties who’s never had a boyfriend before. Her social isolation dates back to her childhood, when she had to wear an unsightly eyepatch thanks to her lazy eye. Her mother, a strict and distant dollmaker, deals with her daughter’s struggles with the dictum “if you can’t find a friend, make one.” In this spirit she gives May a doll named Susan who resides permanently in a protective glass case. May forms an instant, intense bond with Susan which continues into adulthood. Talking to Susan, working as a vet tech at an animal hospital, and sewing new outfits takes up her whole life.

Suzie is a sort of Tyler Durden figure to May – a combination alter ego and nemesis. Like Tyler, Suzie is an avatar of pure archetypal gender, as girlish as Tyler is manly, and where Tyler wants his counterpart to be more fearless, live more dangerously, Suzie wants May to remain isolated, pure as driven snow, sealed inside a box just like her. But whereas Tyler’s status as a hallucination is initially left ambiguous, it’s made clear from the beginning that May’s imagining Suzie. Where Fight Club wanted to draw us in to its narrator’s craziness, May keeps us at a distance, isolating her even from the viewer. Suzie never audibly responds when May talks to her, nor moves, nor does anything except make cracks in her glass case when she gets mad at May.

And get mad she does. Upon finally getting her lazy eye corrected, May feels ready to put herself out in the world and sets her sights upon a handsome mechanic named Adam. She feels particularly drawn to his hands – strong, dirty, blue-collar hands, the last pair of hands the overprotective Suzie would ever want laid on May. Her desire is so strong that she stalks him to a coffee shop and brushes her face against his hands as he naps. To May’s great luck, Adam is a horror-loving film school dropout with a taste for the bizarre, and May’s off-putting and at times boundary-crossing behavior don’t scare him off. May relishes that she can tell Adam gross stories about sewing injured animals back together, and Adam likes that he can bring May into his murder lair and watch experimental films he makes about people eating each other.

Leading lady Angela Bettis plays May with intense homeschool energy, painfully awkward, guileless, naïve, practically vibrating with anxiety. Her skinny frame, homemade wardrobe, and nervous mannerisms make her a perpetual misfit schoolgirl. Even her rebellion against Suzie’s gender expectations still follows a fairly gendered course. May tries to attract Adam by making herself small, pliable, and deferent, adopting his habits, taking up smoking because he smokes, cooking him dinner (mac & cheese, with wine glasses full of Gatorade), earnestly discussing his movies (“I don’t think the guy’s finger would come clean off in one bite. I thought that was a little farfetched”). But despite her best efforts, she ends up driving him away when an overzealous kiss pierces his lip and draws blood.

Depressed, May jumps into a gay fling with her co-worker Polly, but Polly treats her thoughtlessly and eventually tosses her to the side in favor of the long-legged Ambrosia. The unfriendly cat Polly gave her (not-so-subtly evoking the stereotype of a chronically single woman as a “cat lady”) is accidentally killed when May throws an ashtray at her in a fit of frustration. She tries to add some meaning to her life by volunteering with blind children, and even tries to introduce them to Suzie, but in their scramble to “see” Suzie they knock her down, shatter her glass case, and cut their hands horribly and symbolically on the shards.

May’s downward spiral follows a pattern familiar to anyone who’s spent any time on r/TruFemcels. Femcels share a lot with their male counterparts. They share a lot of the same jargon. Both share an enduring obsession with physical features: male incels are prone to claiming that the difference between a happy life and a lonely one comes down to “a few millimeters of bone,” while femcels alternate between bitter rants against society’s fixation on beauty and a frantic dedication to working out, practicing make-up, saving up for plastic surgery, in order to “ascend” (get hot). May shares this fixation herself, having been isolated by her own treacherous body, and she’s prone to lingering on other people’s “pretty” features and proffering unsolicited comments about them: Polly’s pretty neck, Adam’s pretty hands, Ambrosia’s pretty legs, etc. “So many pretty parts,” she sighs, “but no pretty wholes.” The wistfulness in her voice makes it clear she’s including herself in that statement: as much as she wishes she could cut off all the bad parts of herself, she’s stuck with a broken, unlovable whole.

But where male and female incels differ is where they put their anger. Male incels are expulsive: they turn their rage outward, lashing out at the sex that oppresses them and the society that lets them do it. Femcels, on the other hand, turn their anger inward. They have to. If anything, femcels are even more isolated than male incels. Suffused as we are with sexist assumptions about the overwhelmingly powerful male libido, lots of people have trouble wrapping their heads around the fact that a woman can even be involuntarily celibate, least of all male incels, whose worldview depends on women wielding ultimate sexual power. (The Incel Wiki baldly states “It is generally accepted that involuntarily celibate women don’t exist with the exception of women that have medical issues.”) Outside a place like r/TruFemcels, femcels aren’t guaranteed to be able to find anyone to empathize with their problems, and May doesn’t even have that. She only has Suzie, and Suzie ain’t listening.

The other reason femcels generally turn their feelings inward is because women are socialized to do this with everything negative. As femcel researcher Deborah Tolman puts it, “Women will almost always take the blame for their shortcomings…we’re socialized to do that. We’re taught that good women silence aggression, anger and rage and swallow it up, because if we don’t, you know what we get called.” You don’t see femcels fantasizing about a golden age past, where the sexual marketplace provided for all; nor is it likely to occur to a femcel that society needs to be changed to accommodate them. Instead, they blame themselves for their failures. They become whirlpools of self-loathing, swirling forever inward to a darker and darker bottom.

Browsing r/TruFemcels, you don’t get the impression they’re mad at men, at least not in the same way that incels are mad at women. If they ever get mad at anybody besides themselves, it’s other women. “Most men are superficial pigs, that’s nothing new,” says an anonymous femcel, “The thing is that not even other women are our friends… women are competitive as hell with other woman and they are kinda sadist with each other. That’s the reason lookism and the status quo is never changed for women.”

In May’s case, this enmity takes on a literal cast when Polly, a classic “Stacy” (the female version of a Chad) whose advances she succumbed to after losing the man she wanted, leaves her for a hotter woman in a spot of truly Chad-like behavior.

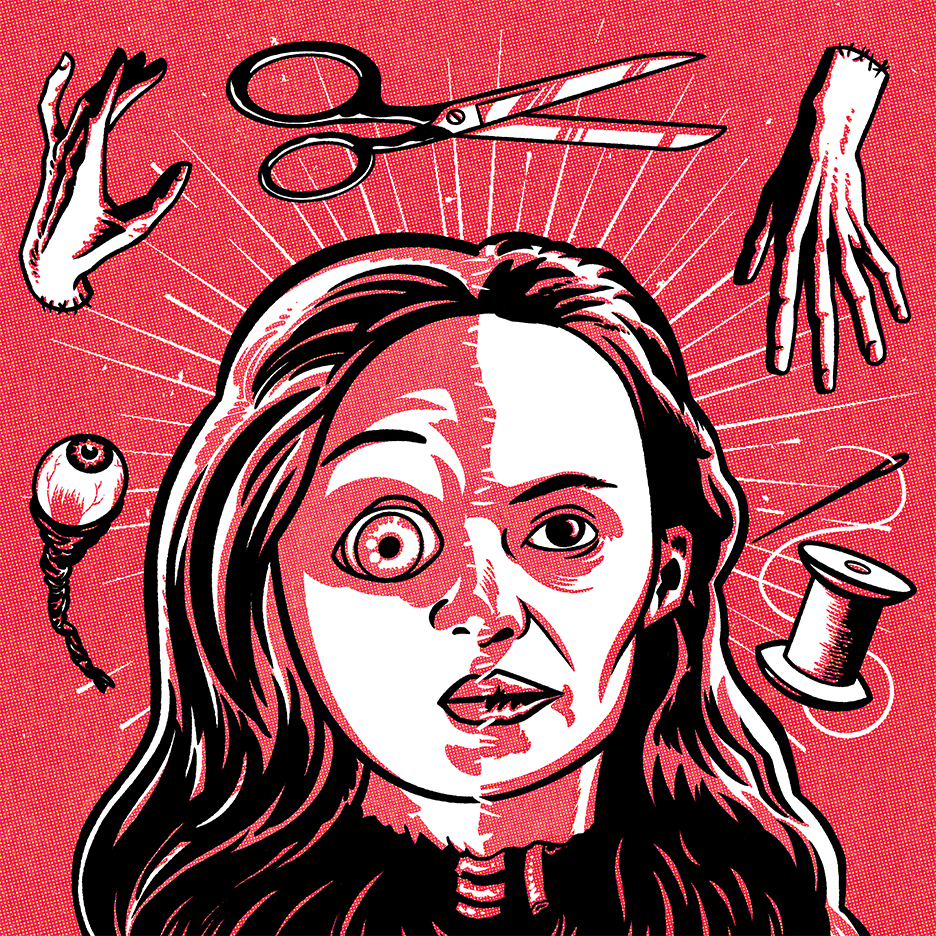

May’s breaking point comes when a punk kid she miraculously befriended at the bus stop opens her freezer and sees her dead cat inside. May tearfully asks if the punk still wants to be her friend, and when he answers in the negative she snaps and stabs him to death with scissors. A montage of all the people who hurt her flashes before her eyes, the camera lingering on their pretty parts, and the logic assembles itself neatly in May’s mind: if you can’t find a friend, make one. “I need more parts,” she says.

That night, which happens to be Halloween, she dons elegant makeup, a dark wine-colored dress like Suzie’s, and a radically different personality, smooth and collected and adult. She drags a cooler to Polly’s house, where she kills her and Ambrosia. She then goes to Adam’s house to kill him and his new girlfriend. Then she lugs the cooler home and after several hours behind the sewing machine, she’s assembled a whole person out of all the prettiest parts of all the worst people she knows.

The fact that May confines her killing spree to people she knows, who hurt her either directly (Adam) or indirectly (the girl Adam left May for), is another point of divergence from the male incel pattern. May doesn’t have a larger point she’s trying to make with her murders. She doesn’t have a mission or a vision. All she has is a bottomless well of pain and a need she doesn’t really understand. She hates the people she kills. But she also loves them – or at least certain parts of them – and wants them to keep on living in a new and better form. As heinous as her acts are, they’re more relatable to the average person than someone who kills strangers over some half-baked internet philosophy.

After May’s new friend “Amy” is assembled, lying lifeless on the table, May’s newfound calm breaks. She forgot to get any eyes, and the person she’s made can’t see her! Sobbing, May takes a knife, gouges out her own eye, her terrible eye, her imperfect, unpretty eye, the eye that sent her down this whole vale of tears in the first place, and places it Amy’s face, screeching “See me!” Her cries bring Amy to life, and she caresses May with Adam’s beautiful hands.

It’s not clear whether this ending, with Amy coming miraculously to life, is happening inside May’s fevered imagination or whether Lucky McKee just decided to end his movie with a fantastical touch. To me, what this represents is the logical end point of May’s isolation. There’s a reason that the existence of incels gets under our skin so much, irrespective of what they do. As much as we rightfully condemn male incels for believing that they’re entitled to sex and companionship from the women of their choice, it also behooves us to note that isolation really sucks. Everyone knows it sucks, but it sucks even more than that.

We humans are social creatures. We didn’t get to become the masters of this planet by having the strongest muscles, or the fastest feet, or the most acute senses. We are pretty smart as far as animals go, but on the wild African savannah that counts for less than you’d think. Our real strength is our sociability, our capacity to form bonds with others. Evolution primed the human species to gather in groups and work together. Our empathy, our altruism, all the things we consider our most noble parts got bred into us over thousands of generations, because those who didn’t have them were abandoned and died. To lack strong bonds is, in some very real sense, to lose your humanity. And when you lose your own humanity, you lose track of some basic truths about being a person and become prone to some real sick ideas. For May, this includes the idea that you can disassemble people and put their best parts back together like Legos. For incels, well, take your pick.

We want to be able to understand this kind of pain, if only to protect ourselves from the consequences, but we have mental reservations about attempting to empathize with terrorists and bigots. Thanks to May, we don’t have to. The movie presents a crash course in incel pathology, in a form we can digest.